Brands, Commodity Aesthetics, and Material Culture in Syria

Interview with Alina Kokoschka about her book Waren Welt Islam (Berlin: Kadmos, 2019), via Zoom on 18 September 2020

Laura Hindelang, Post-Doctoral Researcher, University of Bern

Waren Welt Islam (Commodity World Islam) is a monograph published in 2019 that focuses on the life world of “Islamic” things, consumer culture, and the aesthetics of commodities in the context of Syria, but also Lebanon and Turkey. The author Alina Kokoschka obtained a PhD in Islamic Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin and currently works as a curator at “Die Eiche” in Lübeck. Drawing on Islamic studies, philosophy, and anthropology as her (inter)disciplinary foundation, Kokoschka guides the reader carefully and almost intimately through the topic of her book and the material culture of Syria during the period 2000 to 2011 right before the civil war, a period when she traveled the Middle East frequently. The book offers a very personal and poetic encounter with the topic, where ideas, discussions and connections frequently flow from main text to footnotes to illustrations and back in a palimpsestic and therefore organic way of thinking about things.

Contemplating Waren Welt Islam as a flip-book, one sees the colorful and complex commodity world of Syria up until 2011 flicker past one’s own eye in fast forward; images that contrast starkly with today’s media coverage of the war-torn country. The multitude of illustrations—most of which are photographs that Kokoschka took on site—function like display windows. They allow the reader to look for oneself, to wonder, to analyze, to compare, to imagine, and also engage with the (visual) material. Most importantly, the illustrations offer the reader ways to follow the author’s strolls into side streets, informal markets, and shops, to see things that one would have probably overlooked. Kokoschka sheds light on unexpected treasures in very insightful and novel ways.

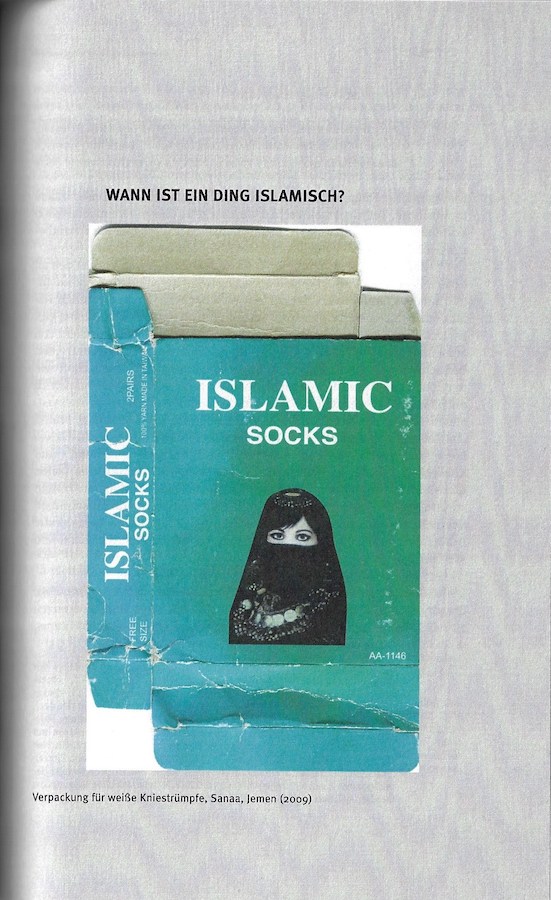

Laura Hindelang: Alina, your book engages with the questions “When is a thing Islamic?” and “What is an Islamic thing?” Why were these question of interest to you?

Alina Kokoschka: During my third visit to Syria in 2006, I first took notice of things with an Islamic connotation that I either had not noticed before or that where new, and I tend to say they were new. I remember a landline telephone on a stand with a lamp and embellished with a glowing photo collage of the Kaaba and the Prophet’s Mosque. The perfect object/thing to put on an old-school telephone table. Objects like these did not belong to the things that are used in Islamic rituals (e.g. prayers) and could not be derived from the Holy Script. This phone was an everyday object and yet it was clearly Islamic. And I thought: What the heck! Later I realized that what had startled me back then was the connection between faith and commodities. Now I know that these spheres have been connected for a long time even before capitalism. Still, I had noticed a change, a new actor in the market. Or a new sphere, where Muslim faith and practice had become visible.

The fusion of these two spheres was not specific to Syria, as Islamization moved from politics into economics in many countries. But Syria showed a very specific development and a specific range of goods. The reason why this was happening in Syria at the time was a larger economic opening of the country under Bashar al-Assad (in power since 2000). The economy became a sphere where new ideas could be tried out, that you could not introduce to the sphere of politics, for example. And commodities could enter public space and convey multiple meanings, religious or political messages. With this opening, also international brands entered Syria.

LH: Islamic commodities, as you wrote in your book, were becoming meaningful through their widespread presence and visuality in the early 200s. These objects not only entered public space but also everyday practices.

AK: Yes, Islamic things became visible in a new manner. Let’s say, Islamic books with their specific aesthetics have been around and on display for centuries, especially in Damascus. But now a new aesthetic was emerging that communicates differently with potential Muslim customers, a language working less with graphic ornament and calligraphy than with images. For example, now the photograph of the Kaaba was printed on an item like a wall hanging, rather than a reduced graphic representation or just the written name. The appeal of objects such as the telephone-lamp resulted from their multiple meanings. People might have hoped for purity of their words while talking on the Kaaba phone, they might have hoped for the blessing of their conversation, and in addition to that it is a fancy decoration signaling a pious lifestyle to potential visitors.

LH: Did this shift from text or script to image also go along with a shift in customers?

AK: Overall objects with a Muslim or Islamic connotation appeared across all socio-economic spheres, but they looked different. It is a combination of socio-economic standing and your self-positioning on the religious spectrum. It is not as simple as to say glitter and brightness stand for “low culture”, for example, and minimalism and natural materials for “high culture”.

LH: Which insights have you gained attempting to find more precise answers to your question “When is a thing Islamic?” beyond common notions such as halal/haram (permissible/prohibited according to Islamic law)?

AK: Halal and haram are legal categories (and actually there are five of these categories). But if you want to understand everyday practices, for many Muslims (in Muslim-majority countries like Syria) these categories do not apply, except for regulations on slaughtering animals, drinking alcohol, and judging behavior. So that did not help me understand commodities better.

Consequently, I tried to differentiate whether these objects with an Islamic connotation were new inventions or if they had a history in Islam. This is important to better understand the degree of Islamization that happens in a society. Some items would have a connection to an older Islamic object. For example, Prophet Muhammed is said to have used the miswāk (wooden stick made from the Salvadora Persica tree) to clean his teeth. Now, there is a toothpaste available that uses an extract of Salvadora Persica. I tried to figure out how far I could go with these categories and to what extent they are useful in explaining the objects I encountered. The toothpaste is not a sign of Islamization of health care articles. It is a modification of an Islamic object. I eventually realized that to do research on commodities in an Islamic framework you need to consider temporality and the biography of objects. For example, a prayer rug is an Islamic thing because it is used to perform a religious duty. We all know the beautiful examples of carpets from Islamic Art museums. But a piece of cardboard can also become a prayer rug for the time it is used as such, for instance, by a shop owner, as I have witnessed many times.

LH: With the arrival of international brands in Syria in the 2000s, you observed and analyzed the rising popularization of branded products and brand fakes. Could you expand on your observations and analysis of brands and brand fakes in Syrian consumer culture?

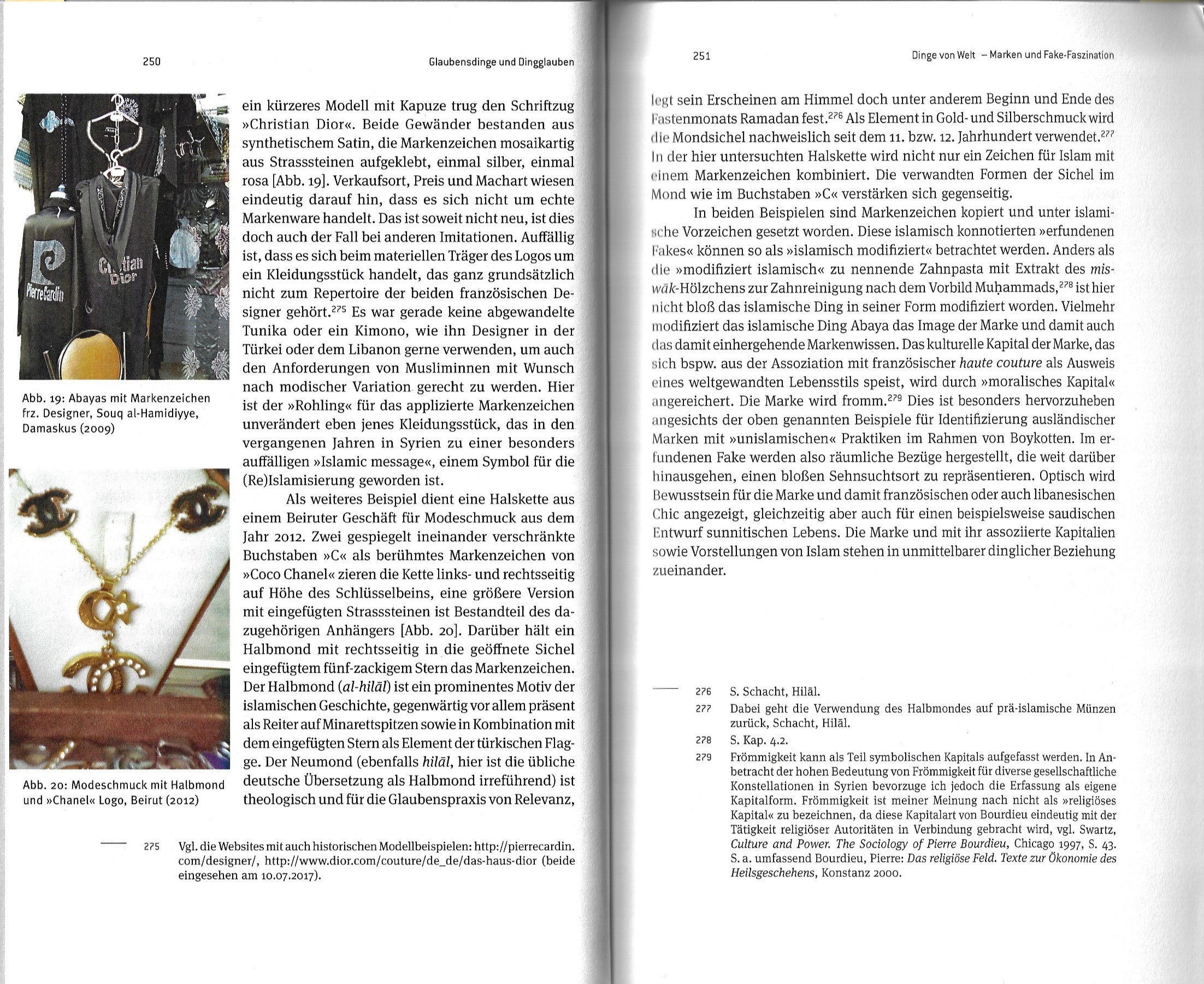

AK: The economic opening was one thing that supported the brand visibility in Syria. The other aspect is that the internet became accessible and people gathered brand knowledge. Although not many foreign brands opened shops in Syria, branded objects started shaping the commodity world. These were in fact fakes but differently than in Europe or the United States, they were sold openly in shops and in markets. And then during the late 2000s, Islamized brand items started appearing. These “fictitious fakes” as I call them, caught my attention. Abayas (loose-fitting full-length robes) started appearing that were decorated with Coco Chanel strass and Louis Vuitton logos or Hugo Boss purses with portrait images of Hasan Nasrallah and Khomeini.

The general explanation for the popularity of those obviously faked brand items was that people in Syria and elsewhere did not have enough brand knowledge to differentiate between the brand and “fictitious fakes” of such brands. This argumentation did not convince me. I think the adaptions we are talking about are more related to the fact that the economic sphere was more open than other spheres. For example, if you wanted to establish a new magazine or publish a book, it was most likely to be censored. But if you produced or sold an Islamized object like that, like a fake branded abaya, no one interfered. People could claim that Hasan Nasrallah, chief of the Hizbollah, is “Boss.” Did the Syrian government not notice? Did it tolerate or even silently support it? Syria, a secular state, has a long history of fighting but also incorporating, sometimes coopting Islam. Prior to 2003 wearing a headscarf was forbidden for schoolgirls. In the military service, soldiers were not allowed to pray. These are just two examples of the earlier “invisibilizating” of Muslim life.

In addition, wearing such an abaya can demonstrate, for instance, that being Muslim, even following a strict Muslim lifestyle, goes along with trendy, cosmopolitan fashion styles from the haute couture houses in France. Upper-class Muslim fashion brands did not yet exist in Syria, in contrast to Lebanon and Turkey, and therefore I read these branded fakes as provisional anticipations or even claims of a potential future fashion scene in Syria. These objects are always open to multiple interpretations.

Spread from Waren Welt Islam © Alina Kokoschka.

For example, the image here of this costume jewelry necklace combines the Chanel logo with the crescent and the star. The necklace shows that brand logos or signs themselves can also be islamized. The crescent is a strong Islamic symbol and it is enhanced by the double C of Coco Chanel’s logo that resemble the crescent shape. You double the (Islamic) symbol by incorporating another (brand) symbol. I assume the Chanel brand was most frequently used because of this resemblance.

Another way of thinking about it would be that Islamic symbols carry some kind of power. There is a relation between religious symbols and brand symbols; wearing the right brand might grant you social respect and a higher position in the social hierarchy. Brand logos have a certain power. And so do religious signs marking you as Muslim in a society where piety can function as a form of capital. Putting religious and brand symbols next to each other empowers them respectively. If we talk about corporate identity, brands are attractive because they reflect a certain identity if one associates oneself with them. They may also carry power that is attributed to a site – think about the Hard Rock T-Shirt in the 1990s. Wearing a T-shirt from the Hard Rock Cafe Los Angeles in Germany was something that held meaning because it originated from a specific site and said: I went to LA. Similarly in Islam, symbols and textiles can bear a strong spatial connection. Divine blessing (baraka) is closely related to sites. It is believed to be contagious and can thus be transmitted from the site to the textile and then to the body through contact. So objects also have the power to transmit this blessing from a site onto a person via an Islamized object referring to this holy site.

LH: I found especially insightful how you explained this popularity, the social appreciation for such “fictitious fakes,” by drawing on Koranic manuscript traditions. Could you tell us more?

AK: Yes, instead of disregarding these objects as false fakes, I thought about ways to think about them from within. I thought: What is the meaning of a copy in Islam, historically? Also, is the original initially something not to be touched, copied, altered? Or is it something that invites you to engage with it and leave your traces in the process? In Islamic manuscript tradition, the scribe became traceable by his (or her) distinctive style of handwriting. That the work was a copy was immediately recognizable. Moreover, the traditional layout of Koranic manuscripts positions the Koranic text en bloc in the center and puts the exegesis, the later added commentary and questions, around it. The exegesis thus frames and contrasts the horizontal Koranic text through diagonal or curved writing. So, coming back to our context, the brand logo is the original and the context you apply it to, which is an Islamic context, becomes the commentary. It basically says about the person who wears it: If I would engage with French fashion, I would do it in form of a Chanel abaya. What we see here is a form of material citation: A good that you adopt from one context to integrate it into your Islamic context is a form of citation.

LH: The citation becomes a process or gesture of positive affirmation?

AK: Yes, also the copy becomes a form of positive approval of the original and the (ficticious) fake.

LH: The new commodity aesthetics came not only from brands/fakes but also through the proliferation of plastic and very bright colors and neon lights. You can imagine, given my own research interest in petro-cultures, I also read the book looking for hints on petro-based products such as plastics (nylon, polyethylene etc.).

AK: I am really happy that you raise this topic as I have never really thought about polyester, plastic, or fossil energy in this context. All of this plays such an important role in my research but I have never traced it back to petroleum.

LH: As I work on iridescence as a concept describing the aesthetics but also effects of petro-modernity, I’m interested in these moments of colors entering various media or visual culture in general. Synthetically enhanced colors, but also brightly colored plastics therefore interest me. You talk about the shift in commodities, from the wooden squeezer produced in a local workshop, perfectly functionally designed, to a plastic fish with an illuminated image of the Dome of the Rock that a Chinese factory produces and sells across the world. To what extent do plastic things and screaming colors enter the commodity world of Syria?

[Caption:] Clownfish-shaped lamp with a glowing image of the Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem)which is regarded as the third holiest site in Islam. © Alina Kokoschka.

AK: Syria has a long-standing tradition of exchanging goods with China given their shared socialist orientation. So they have a stable trade relationship but the materiality of the goods has changed; once there were mostly goods made from tin or enamel, and this shifted to plastic, which consequently made the products more affordable.

However, plastics and very bright neon colors in Islamic things are not necessarily considered to be cheap. I argue that we can also think about them as a form of materializing, visualizing thoughts about paradise and afterlife in this world. The vision of paradise plays such an important role is Islam and historically there are certain materials limited to paradise that are not to be used in this world from a theological point of view, like silk or crystal in certain contexts. I would argue that when you walk through these shops with a Muslim target group, where it is all so bright and color-lacquered plastic, it is not cheap taste, not kitsch. Rather, it is an abundance that you take from another sphere, a sphere that you are not allowed to duplicate. So you transform it into a material that is allowed. You can praise the beauty of this divine sphere by giving it a materialization in this world.

Light also plays such an important role in Islam, also as a symbol of knowledge. The light of God (al-nūr) shines into the darkness of ignorance and what is of special interest here, is that it is considered a heatless light. Now take neon light for instance: It is cheap and a very cool light, attractive for people living in a warmer climate than in Europe, of course also in non-Muslim countries. Still, there is a positive attraction to neon light that stems from this religious connotation.

LH: In your book you also argue that a shop owner’s abundance in products and his perseverance to show items to potential customers relates to the idea of being pious, being hard working and also successful in your business. With cheaper materials such as plastic (produced by fossil energy, and crude oil derivatives), it appears to me that this maxim is easier to achieve.

AK: Yes, there is a connection. Also, I often observed that colorful abundance comes in objects of faith while the rest of the apartment, for example, is kept really simple. It is somehow a marker, a way of celebrating creation.

LH: Let’s talk about images. When I was reading your book I often got the sense that the images you included, your photographs taken of streets, vendors, shops, and things in Syria, Lebanon and Turkey, displayed a form of “thinking-in-images.” On a practical, yet methodological level, what did it mean to roam around Damascus with a camera and photographing things that most people would probably not have considered noteworthy, let alone picturesque. How did your surrounding react and which strategies did you develop?

AK: It was surprisingly easy! I expected it to become a problem, but people usually agreed to let me photograph their products or shops. Syrians also take photographs and film inside of mosques (not during prayer time), so using my camera in shops and on streets was not an issue.

LH: How would you describe the relationship between text and image in your research and your methodology?

AK: In general, I took notes, minutes of my thoughts, I wrote a field diary and did participant observation, all of which I consider valuable (written) sources. But when I started to go through the photographs I had taken over all these years over and over again, I saw something new almost every time, like a detail I had missed before. My book is not just about commodities and their aesthetics, but also about the contexts and environments in which these commodities exist and are sold.

LH: Something you refer to as “situating the object” instead of “following the object” in your book, right?

AK: Yes, and this is an outcome of working with these images. I took these photos in stores, markets, and malls. When I looked at them later, each time I would see something new, elements that would help me understand how the commodity connected to the locality, the shop, the neighborhood and other commodities. Subsequently, I realized that these images had to be part of the book as “image based footnotes” in order to make my way of thinking and researching more transparent to the reader. And I also find it sad that people collect vast archives during their research process and most of it eventually remains hidden. Moreover, I wanted to take the reader seriously and give him or her the possibility to develop his or her own thoughts in relation to the images and possibly even question my writing and analysis based on the same material I used.

LH: Reading the book and contemplating the images, as a reader, made me especially aware of the plentitude of things, of everyday life in Syria. It contrasts the images on Syria that circulate today in light of the civil war and I think that makes your photographs even more valuable.

AK: Even before the civil war, the image of Syria to many was sort of “grey” and now it is grey and destroyed. But the fact is I experienced Syria quite differently and I feel the images are helping to pay justice to that liveliness and colorfulness I saw.

LH: How did the image-based open science platform Hawass – Contemporary Islamic Aesthetics, which you founded, emerge from your research? What are you aiming for with this initiative?

AK: During the research process, I felt that I needed to find out more about the contemporary objects, the commodities and images I am dealing with; information that I could simply not find in the usual sources. Because, things are either to new or, the even bigger problem, many things are being ignored because they don’t fit the idea of the “authentic” Islamic thing or the “authentic” Muslim practice. Moreover, you can find symbols like the two-pronged sword zulfikar (dhū al-faqār) in Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey but the attributed meaning changes wherever you go. There is a nucleus of meaning that remains stable but then context-specific connotations are made and with it come different groups of people who wear or use it. There is still so much to explore, I am sure that many people who work on contemporary Islam feel the same.

With this in mind, I eventually collaborated with a bi-scriptural design office4 and they helped me create the website Hawass—Contemporary Islamic Aesthetics. It is a contemporary archive, virtual showroom, and open research network in Arabic and English. Even today, whenever I go somewhere and see bi-scriptural writing, a Ramadan calendar that comes with a unicorn, or a Hezbollah-backpack, I take a photo and add it to the Hawass archive and develop a taxonomy for it, also to provoke new thoughts on how we categorize and talk about contemporary material culture in a Muslim context.

LH: What means “open science” to you in the context of Hawass and what importance, what challenges do you credit it for MENA scholars who work image-based?

AK: The open science aspect inherent in Hawass is to open your archive and to share thoughts and ideas at a stage when you haven’t published yet, basically visualizing and disclosing the many version of a published article, the editing or the thinking process behind (academic) work. Also, all the ideas that often get lost in the process of streamlining a text. People who are not in academia might get interested, too, given that images can make it easier to access topics. Hawass might offer a safe, non-hierarchical space to share, exchange, and develop these ideas collectively, without losing authorship or without feeling judged.

LH: So whoever is interested can participate in Hawass?

AK: Yes, people can upload their own photographs and add information on existing photographs, also articles are welcome. I would be happy to receive contributions!

Biographies

[Left] Alina Kokoschka, who holds a PhD in Islamic Studies (Freie Universität Berlin), investigates contemporary Islam at the intersection of things, images, and script. Beyond her philosophically informed approach, Kokoschka has a keen interest in documentation. Hence, she founded the open archive Hawass. Contemporary Islamic Aesthetics. As a curator she currently works for the museum and columbarium Die Eiche (Lübeck), focusing on the relation of art and grief, objects and loss.

[Right] Laura Hindelang is a Post-Doctoral Researcher at the University of Bern, Department of Art History. Her forthcoming book (De Gruyter) focuses on Kuwait's urban transformation and evolving urban visual culture in the mid-20th century in relation to questions surrounding the (in)visibility of petroleum. She is a member of Manazir’s managing committee and of Manazir Journal’s advisory board.

How to cite this review: Laura Hindelang, "Brands, Commodity Aesthetics, and Material Culture in Syria", Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA Region, 14 October 2020, http//www.manazir.art/blog/brands-commodity-aesthetics-and-material-culture-syria