Engraved on the Heart

Remembering Menhat Helmy, Egypt’s forgotten pioneer

Karim Zidan, investigative journalist, creative writer, and freelance translator

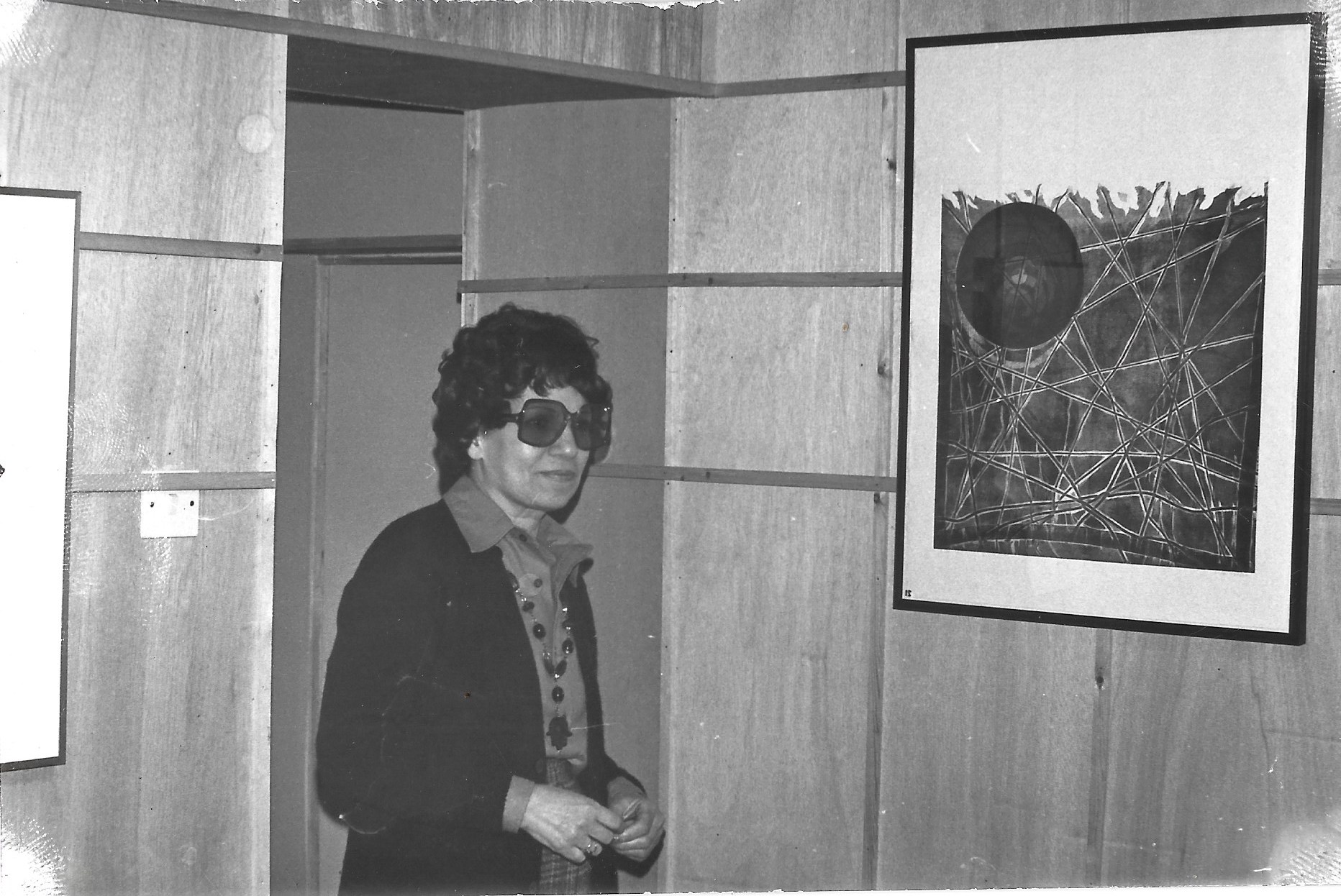

In 1972, two years following the death of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Arab Socialist Union Central Committee hosted a unique exhibition dedicated to the late president, his ideas, and the significant social and political changes that took place during his historic tenure. Titled “Gamal Abdel Nasser – Exposition1,” the exhibition brought together dozens of Egypt’s finest artists from various disciplines and invited them to produce works that demonstrated Nasser’s revolutionary thoughts and influence, including Hamed Nada, Gazbia Sirry, Zeinab and Gamal El Segini, Seif Wanli, Effat Nagi, Mostafa El Razzaz and Omar El Nagdi.

Nestled amongst these renowned artists and their impressive works is a striking painting titled Farewell (fig. 1) – a somber oil on canvas work depicting endless rows of faceless people bidding farewell to a bygone age. It is a subtle piece painted by an artist who spent the vast majority of her career capturing the essence of life in Egypt, an artist who rose to prominence as a pioneer in the world of Arab graphics, an artist who would soon be lost to history and to the annals of old catalogues and out-of-print books.

Menhat Helmy produced her art at a pivotal point in Egyptian history. She emerged during a golden age for modern Egyptian artists and cemented herself as a female pioneer in the fertile world of graphics. Her etchings, paintings, and woodcuts are characterized by their geometric harmony, uncompromising precision, and their ability to call forth the collective memory of Egyptian society during the 1950s–1960s. Every work is an extension of the artist’s sensitive nature and her undying pledge to use her talent to provide a voice to Egypt’s unseen majority. Understanding Menhat Helmy’s work begins by understanding both the thematic importance and historical significance of her art.

England to Egypt in Etchings

Born in 1925 in Helwan, Egypt as a middle child in a family of seven sisters and two brothers, Menhat Allah Helmy stood out amongst her siblings through her artistic talent. Despite being the daughter of a legal consultant in the Ministry of Education, which offered limited exposure to visual arts at a young age, Helmy’s father encouraged her to explore her talent and pursue higher education in fine arts. At the time, state education was the primary avenue for aspiring artists to become exposed to visual arts in Egyptian society2. Helmy attended Cairo’s High Institute of Pedagogic Studies for Art alongside her sister Raaya Helmy and fellow Egyptian artist and longtime friend Gazbia Sirry. Some of her teachers during that time include Marguerite Nakhla, one of the finest Egyptian painters of the 20th century, and Kawkab Saad. Helmy graduated in 1948 but opted to stay on for another year to receive her teaching diploma.

In 1953 – approximately one year following the July 1952 military coup led by Mohammed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser that overthrew King Farouk and Egypt’s monarchy – Helmy was awarded a government scholarship and traveled to London to continue her education at the Slade School of Fine Arts. She was joined by Sirry the following year, making them the only two Egyptian women studying at the prestigious school at the time.

Slade proved to be a pivotal time in Helmy’s development as an artist. Not only was it her initial exposure to the world of printmaking, it was also where she learned life drawing and classical painting in the form of portraits and nude figures. Life drawing was the most important component of the Slade curriculum – students began by drawing from the Antique in the cast room until judged by their professor as competent enough to progress to the life room. There, students spent the majority of their time training in objective observation from life and draped models, progressing to painting only when their professor deemed them competent. There were lectures on anatomy and perspective, all of which influenced Helmy’s approach to painting and drawing in the 1950s. Her nude paintings in particular demonstrated the skills she acquired to render subtle shifts in skin tone, juxtapose her model with the domestic drapery and furniture surrounding them, and the way light interacts with the model. Several of these works – small-scale nudes and half-length portraits steeped in Slade’s characteristic emphasis on isolation – were displayed at the Menhat Helmy retrospective show at Gallery OFOQ, Cairo in 2005, less than a year following the artist’s death.

During her three years at Slade, Helmy studied painting and design before settling on etchings as her preferred medium. She began to experiment with different plates, using copper, zinc and wood to produce black-and-white prints that distinguished her work at a young age. Inspired by her new medium of choice, Helmy journeyed across England during her three years at Slade, exploring London’s parks, churches, and rivers, and travelling to places like the Isle of Wight and to small towns along the countryside. She carried a small sketchbook, which she used to lay the foundations for her later prints. Influenced by European masters such as Francisco de Goya and Albrecht Dürer, Helmy used aquatint to produce areas of tonal variation in her etchings, which allowed her to create detailed depictions of the world around her. Her dedication to the craft of printmaking did not go unnoticed, as the Egyptian artist went on to win the Slade Prize for Etching in her final year at the school.

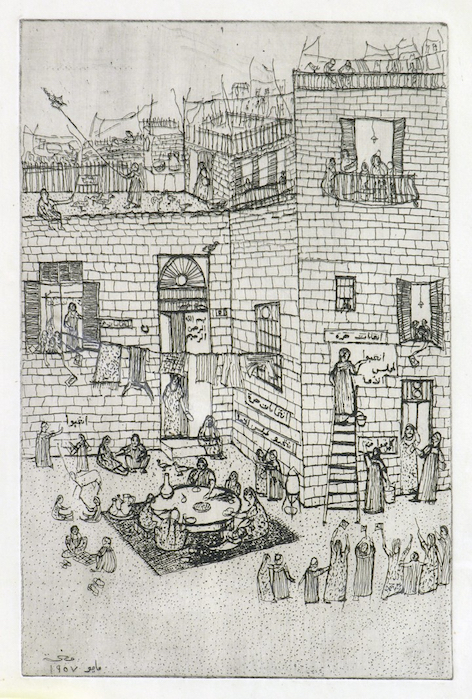

Helmy graduated from Slade in 1955 and returned to her homeland at a time marked by social upheaval, geo-political tension and the rise of Arab nationalism. She decided to use her newfound medium to document the historic changes taking place around her. Among these works is a black-and-white etching on zinc depicting a village neighbourhood preparing for the 1957 parliamentary elections (fig. 2). There are misshapen and dilapidated buildings, pigeons and other fowl nesting on the roof, and signs spelling out the words “Free Elections” and “Vote for the National Assembly.” There are also women leading the process, hanging up signs and rallying support – a feminist aspect that became a common theme in her work. One gets the sense that change is in the air – a sense of hope that trickled down to the masses who believed in their country’s future. Helmy manages to capture the joy of the occasion through the eye of Egypt’s poor, the same segment of Egyptian society that were never given a say in their country’s governing.

Not only did these historical etchings provide a small window into Egypt’s forgotten past, they also shed light on the country’s downtrodden majority and the districts they resided in. Much as she did during her time in England, Helmy traveled around her native land and recorded everything she saw in her extensive catalogue of etchings. There were agricultural landscapes being worked by peasants, fishermen on the Nile, workers labouring inside brick factories, and alleyways reminiscent of the scenes portrayed in Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz’s stories. These detailed scenes depicted life in Cairo at the time and reflected the artist’s inherent socialism and her insistence on using art as a platform to empower Egyptians.

Between 1956 and 1966, Helmy produced more than 40 black-and-white etchings depicting life in Egypt, inspired by scenes she witnessed while teaching at the Institute of Fine Arts for Girls in Bulaq, Cairo. Apart from a handful of paintings, this period of Helmy’s career was almost exclusively dedicated to etching realistic scenes. Though graphic art forms such as etchings had been taught in Egypt since 1934, it would take approximately two decades for it to be seen as a legitimate art form3. Along with likes of Abdalla Gohar, Omar El Nagdi, Saad Kamel, Hussein El Gebaly, and Mariam Abdel Aleem, Helmy was recognized as one of the pioneering artists4 who dedicated themselves to the practice. Helmy’s black-and-white etchings were critically acclaimed5 for their remarkable complexity, as well as for their incredible difficulty in realization. Helmy was one of the first artists to engrave entire scenes into her work, replicating the effects of sketches and elaborate drawings on zinc before transforming them into prints.

Helmy’s pioneering work did not go unnoticed. After participating in most local exhibitions from 1956 onwards, she won the Cairo Production Exhibition Prize in 1957 and the Salon du Caire Prize in 1959 and 1960. She also participated in local exhibitions such as the Exposition de Printemps in 1960-61, where she displayed her work alongside the likes of Abdel Hadi Al Gazzar, Samir Rafi, Ramses Younan, Inji Ifflatoun, and Gazbia Sirry. Helmy was then invited to participate in over a dozen biennales around the world during the 1950s and1960s, including the Venice Biennale in Italy, the Alexandria Biennale for Mediterranean Countries in Egypt, and the International Print Biennale, in Krakow, Poland. However, it was at the Ljubljana Biennale for Graphic Arts in former Yugoslavia where Helmy’s work truly shined.

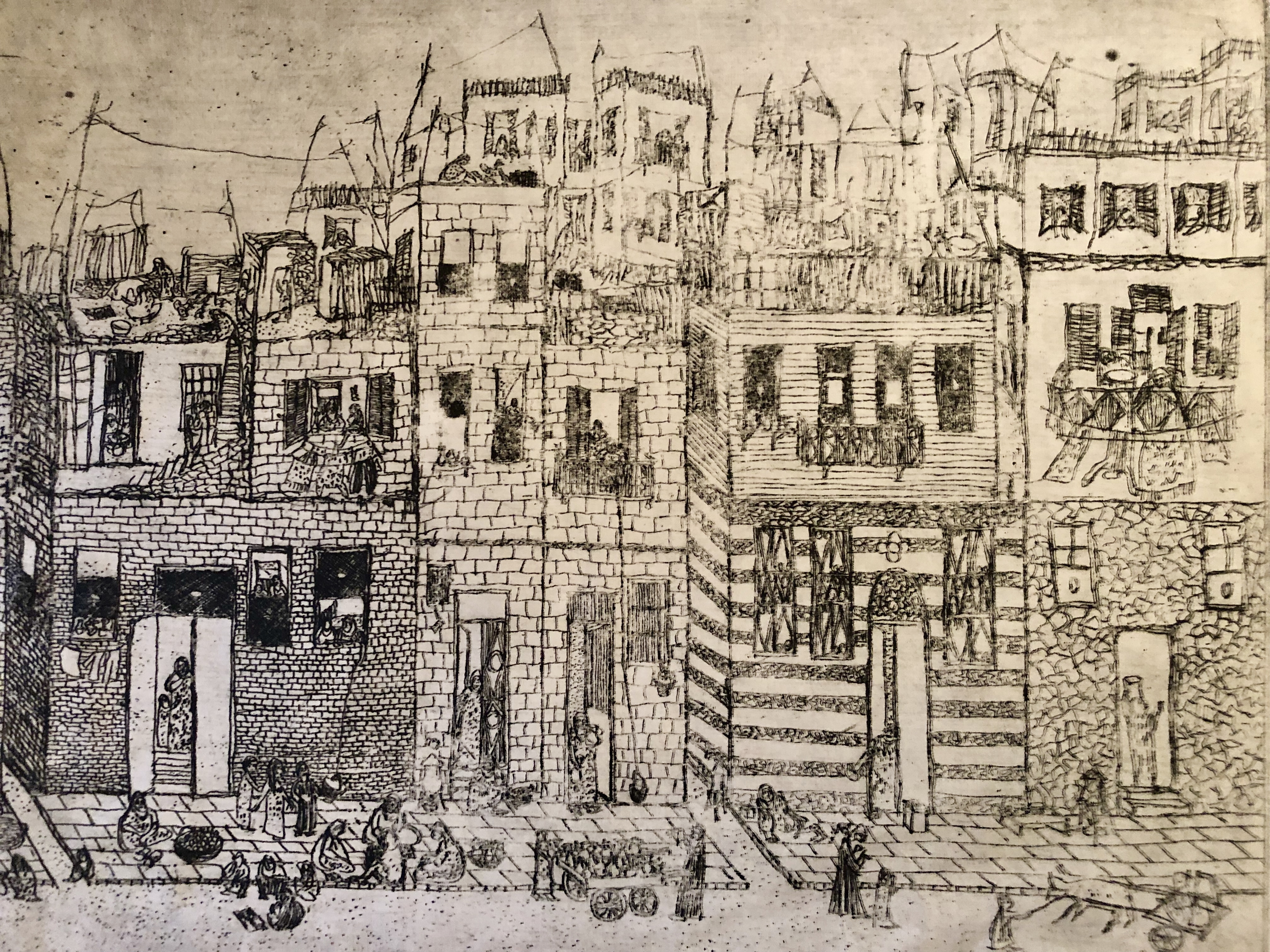

Helmy won the Ljubljana Honourary Prize in 1961 for her Old Cairo (fig. 3) print, which was displayed at the Ljubljana Biennale for Graphics that same year. The print depicts a narrow alleyway in Cairo’s Bulaq neighborhood packed with a dense row of apartment buildings. It is a work brimming with life. There are locals strewn across the street and hanging out of windows and balconies, street vendors selling fried snacks and children playing — all of which was presented in a detailed and geometrically sound composition. It is also a deeply socialist work embedded with a sensitive understanding of Egypt’s majority that characterize Helmy’s etchings. Bojana Videkanic reiterated this statement in her research6 on the Ljubljana Biennale, stating that “her representations of the masses are not there for political nationalistic exaltation; rather, they signal people’s sense of self and identity as collectivity created through everyday social bonds of labor, play, and caring.” (Videkanic 2020)

Helmy would later be made an Honorary Academic at the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno for her work displayed at the Ljubljana Biennale. This achievement was reported in local newspapers at the time. She would continue to create more elaborate black-and-white etchings until 1966, when she held her first solo exhibition at the Akhenaton Gallery in Cairo. The exhibition featured 55 of her etchings created between 1955 and 1966 — an eleven-year labor of love that encapsulates the length of time it took her to compile an extensive repertoire of works.

After establishing herself as an award-winning and acclaimed etcher both at home and on the international stage by the late 1960s, Helmy decided to pivot away from the black-and-white etchings that characterized her work, instead challenging herself to create powerful political paintings and abstract prints, the latter of which were ahead of their time in the Egyptian art scene.

Abstraction in the Age of Arab Nationalism

The period between 1967 and 1973 brought the winds of change to an Egypt at the height of pan-Arabism. The 1967 Arab-Israeli war – commonly referred to as Al-Naksah (The Setback) by Egyptians – was a humiliating defeat for Egypt, Syria and Jordan and highlighted the Arab states’ poor leadership and military strategies. Israel crippled its opposition with a well-enacted strategy, allowing them to seize the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula including the West Bank, East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria. Nasser subsequently resigned in shame but was reinstated after nationwide protests against his resignation. Nasser remained in power until his sudden death on 28 September 1970.

As with many artists and intellectuals in the region at the time, to suggest that Helmy was profoundly impacted by the events that unfolded between 1967 and 1970 would be a gross understatement. Throughout the course of a career that spun nearly four decades, the aforementioned three-year period was the only time that Helmy did not produce any new artistic works. This would change in 1971. Inspired by the tumultuous events of the previous years, Helmy turned to abstraction for the first time and painted a piece depicting the War of Attrition, which lasted from 1967 until 1970.

Titled Exchange of Fire the painting shows the military strikes taking place between Egypt, depicted in brown, and Israel, depicted in green, with the Red Sea as their separation, in blue. There are red lines streaked across the painting, fired from all sides like cannons at war. Though they may appear random, there is a remarkable spatial synergy present in the piece – a distinctive characteristic that came to define Helmy’s work. Even her pivot to abstraction was geometric in nature, rooted in deep spirituality and inspired by Islamic art. While she continued to free herself from the continues of figurative work and realistic depictions of her surroundings, she never parted from her love for symmetrical and mathematically-minded art.

Fueled by the turbulent political climate and further drawn to her brush and canvas, Helmy painted a second piece in 1971 titled The Children of Bahr Al Baqar (fig. 4), which portrayed the primary school bombing that took place in the Egyptian village of Bahr El-Baqar (south of Port Said, in the eastern Sharqia governate) on April 8, 1970. The school was bombed by the Israeli Air Force, killing 46 children and injuring dozens more. The entire school population at the time was 130 students split between three classrooms. Israel later claimed that they thought that the school was an Egyptian military base.

The painting is a classic Menhat Helmy composition: a sea of faceless people, their bodies formed out of rectangles, their heads out of circles, conjoined together in perfect symmetry like an intricate puzzle. There are exactly 46 bodies, one for every child that died that day, strewn across the canvas. It is grim, powerful, and steeped in emotion. You can almost feel Helmy’s pain resonate through the paint, as she tried to make sense of the senseless violence and the bombing of her homeland.

In 1972, Helmy relocated back to London after her husband, Abdelghaffar Khallaf, became the medical attaché for the Egyptian embassy in the United Kingdom. The couple travelled with their two daughters, Nihal and Sara, and settled in Richmond. Helmy enrolled part-time at Morley College, an adult education college where she continued to study printmaking, mainly intaglio. Helmy and her family remained in London until 1978, during which time the artist gradually merged her newfound affection for abstraction with her love of printmaking — a combination that cemented Helmy’s place as an Egyptian pioneer.

At first, Helmy continued to create political pieces marking key occasions like the Yom Kippur War in October 1973. Two of her etchings at the time, titled Reconstruction and October Crossing reproduced the moment when the Egyptian army successfully crossed the Suez Canal and advanced into the Sinai Peninsula. While a ceasefire was eventually brokered, Egypt was able to gain a stronghold on the east bank of the Suez Canal and used it to negotiate the return of the occupied territory. This was widely seen in Egypt at the time as a psychological and moral victory that compensated for the humiliating defeat six years earlier. Though Helmy was in London during the time of the war, she commemorated the victory in two separate etchings that captured the extent of her fervent nationalism. These are arguably the most overtly political pieces in Helmy’s entire archive of works, lacking the subtle indicators that were more representative of her work. Thereafter, she sought to rid her work of personified elements and experimented with more elaborate compositions using multiple plates, aquatint and acid to create coloured graphics that brought out only the most essential elements.

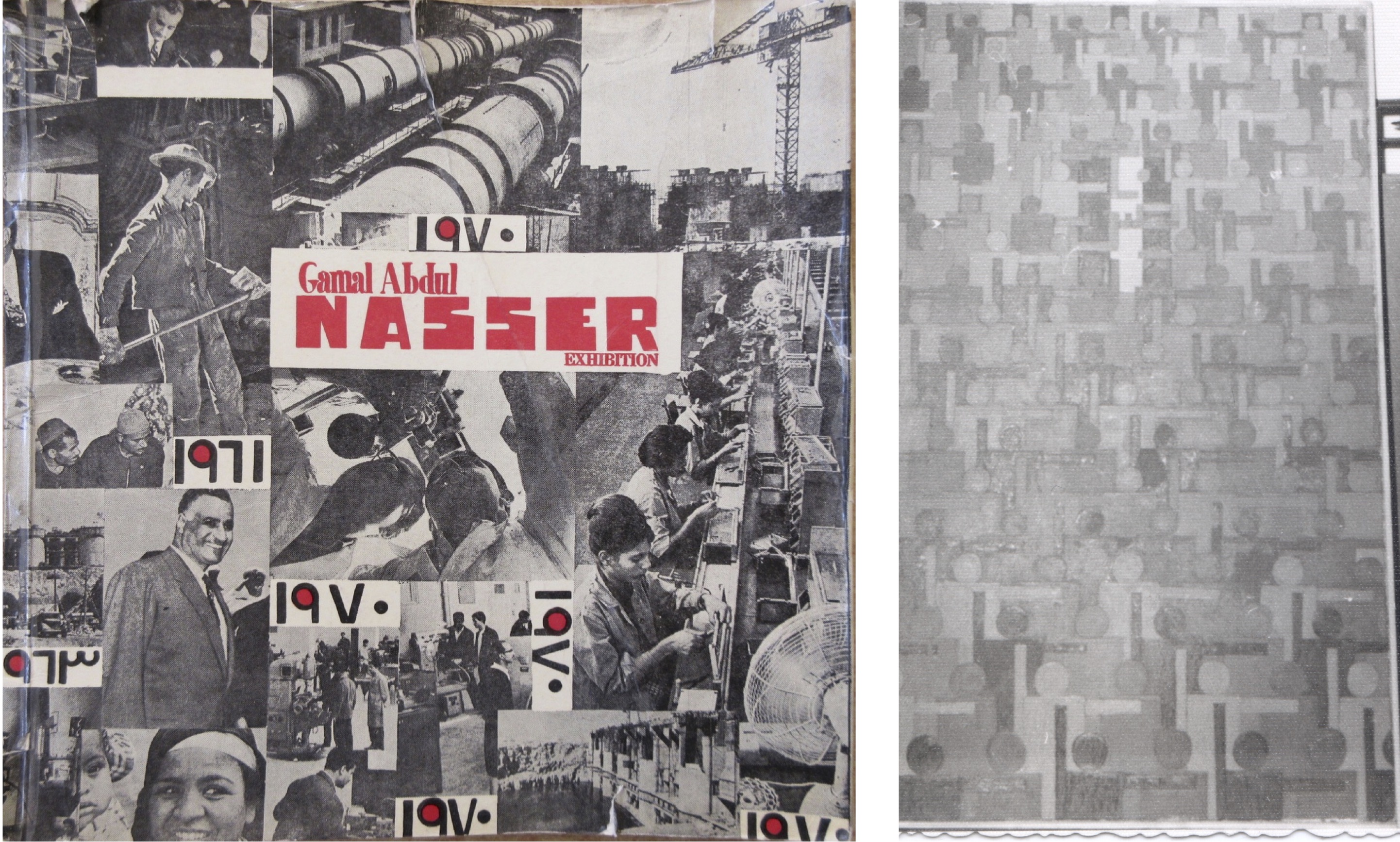

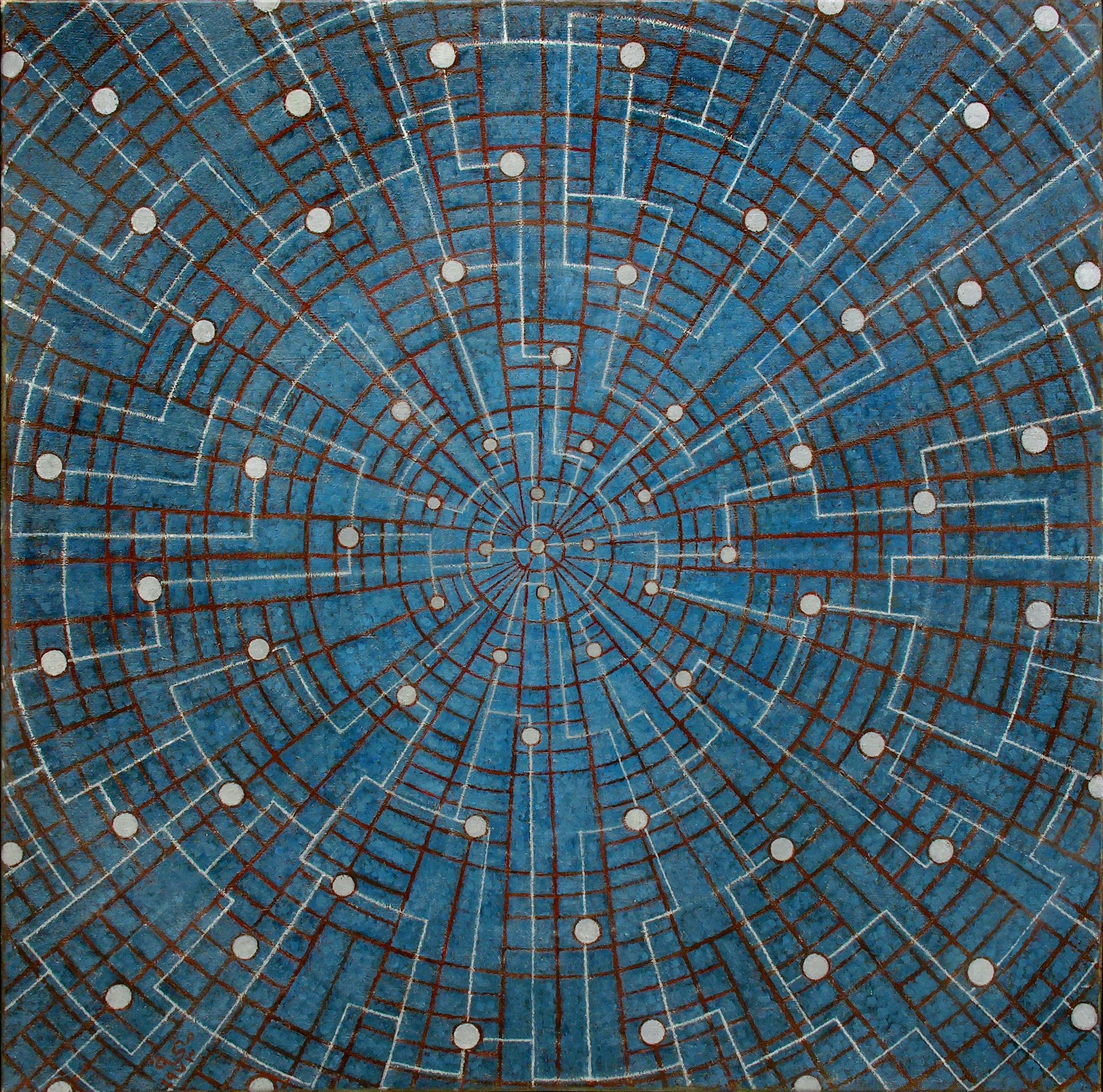

Set free from the confines of representational art, Helmy became inspired by the ever-changing world around her. She was fascinated by the exploration of space and technological advancements such as the computer, which were reflected in her paintings and etchings at the time. In 1973, she painted one of her finest works titled Space Exploration (fig. 5), a geometric showpiece that opens a window into the night sky and the universe beyond. She would later design a coloured etching based on the painting, which she then printed in various colours. This masterful painting and subsequent etchings are some of the finest and most important pieces in Helmy’s collection and the perfect encapsulation of the final portion of her artistic career. It has since been acquired by renowned collector Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi of the Barjeel Art Foundation and is currently touring the United States as part of the Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World 1950-1980 exhibition, which began on January 14, 2020, in New York City.

Over the course of the next decade, Helmy continued to purify her art of the residue of visual reality. Influenced by Islamic and Pharaonic art, Helmy used geometric abstraction as an avenue to connect science and art with her inherent spirituality. There is harmony and rhythm to her work – a sense of comfort and tranquility that is the result of endless hours of patience and deliberate printmaking artistry. In many ways, Helmy succeeded in creating a pictorial language with her abstraction, one rooted in simple geometric forms presented in various non-illusionistic compositions. It is elemental, pure, and highly emotive.

Unlike organic abstraction which prioritized loose compositions that emphasized the artist’s expressive brushstrokes and the unpredictable nature of the work-in-process, geometric abstraction – especially the etchings Helmy produced in the twilight of her career – required extensive planning and near-perfect precision in order to create shapes that affect or inspire their audience. It can be minimalistic, architectural, playful, or even mystical. She achieved this without succumbing to the dry nature of geometry, instead creating compositions that took viewers on a journey towards an unknown destination. Her art was non-objective, pushing viewers to look within themselves to find solace.

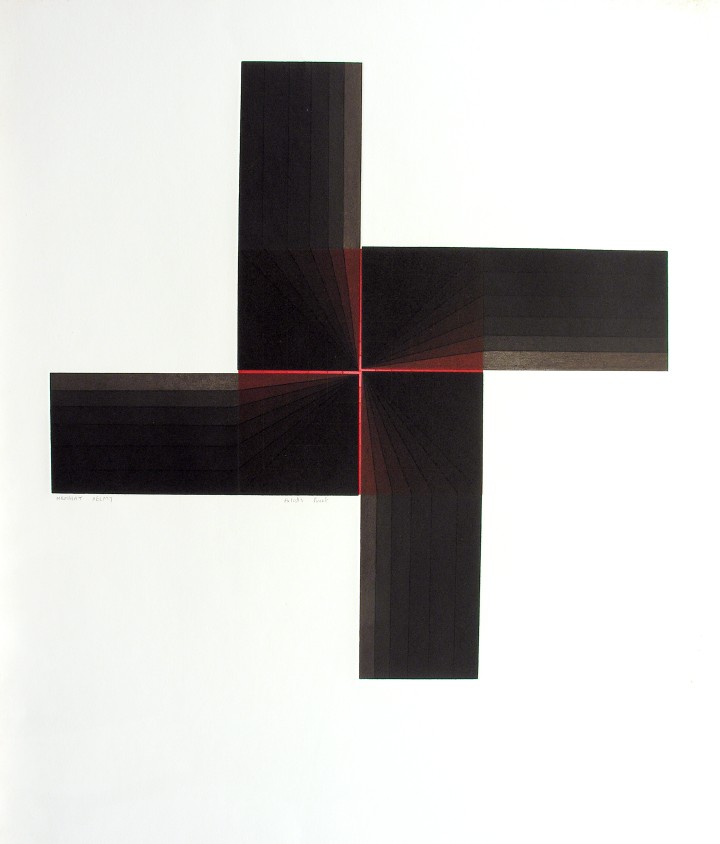

In 1978 – the final year of Helmy’s second stint in London – she composted a coloured etching titled Red Line (fig. 6), a vivid testament to the spirituality of her geometric abstraction. The work appears simplistic, reminiscent of Kazimir Malevich’s suprematist phase. And yet, it is not so much the shape as the lines running through it in perfect synergy, all navigating towards a fine point at the heart of the piece. It asks you to step inside the work and follow the red line towards the light, which grows brighter the further you go. It is a path to salvation, to redemption, to serendipity.

After hosting a solo show of her abstract coloured graphics at the XVIII Gallery in London in 1978 to much press and acclaim, Helmy returned to her native Cairo, and to a new audience ready to receive her work. In 1979, she held another solo show at the Goethe Centre in Cairo, which was attended by renowned artists, politicians, and collectors. While her work was well received, it was not without its critics. In a handful of anonymous messages left in her visitor’s logbook from the event, Helmy’s work was criticized as “mysterious,” “lacking clarity” and for not being “nationalistic” enough. She was called a “Western imitator,” while another expressed that she did not deserve to be referred to as an artist. To a certain extent, these criticisms reflected the nationalistic fervor surging through Egypt at the time. That year, Egypt and Israel had signed a peace treaty following the controversial 1978 Camp David Accords, a decision that was highly unpopular amongst Arab states. Egypt was suspended from the Arab League between 1979–89, and several Arab leaders severed diplomatic ties to the country This dissolution of Arab nationalism led to a resurgence of Egyptian nationalism, which trickled down to all aspects of society, including the Egyptian art scene.

However, the criticism levied against Helmy also emphasizes how ahead of her time her abstract art truly was. She displayed her creations at a time when artists such as Hamed Nada used their work to articulate dark political themes and social commentary in a raw, almost crude form. While Helmy’s earlier work was representative of this political style, her later abstraction stepped far outside its bounds and into new frontiers that were yet to be extensively explored in Egyptian art. Therefore, those who were looking for political commentary in her abstraction viewed it as “mysterious,” while others saw her etchings as a mere Western imitation. As argued throughout the course of this section, those criticisms could not be further from the truth. While Helmy may have learned the art of printmaking in England, her inspirations were both Islamic and derived from her ancient Egyptian ancestors.

***

When Menhat Helmy returned to Egypt in 1979, she purchased a printmaking press and a studio space that she planned to use for years to come. Then, her career came to an unexpected end. Helmy’s lungs began to suffer after years of inhaling fumes from the printmaking process. Then, in 1988, her husband of more than thirty years passed away. Torn from the partner she cherished and deprived of the art that brought her the most joy, Helmy decided to retire. Her final print is dated 1983 – a full 21 years before her own passing away in 2004. We can only wonder what else she could have produced during that two-decade period.

Despite her career being cut short, Helmy left behind an extensive body of work made up of sketches, drawings, portraits, paintings, woodcuts, and various styles of etchings. She also left behind a legacy as a pioneering female artist who bucked against artistic trends and revolted against the customary traditions of figurative painting popular in Egypt at the time in favour of experimenting with new mediums. Her portfolio is a journey into an Egyptian woman’s desire to capture the world around her, and a story about her triumph in the age of political turmoil, man-made miracles, and the male chauvinism that continues to threaten the art world.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Fathi (1985). Egyptian Graphic Art (Arabic). Cairo: General Egyptian Book Organization.

Arab Socialist Union (1972). Gamal Abdel Nasser Exposition (Arabic). Exh. Cat., Cairo: Secretariat for Religious Affairs, Culture & Information, Section of Culture.

Gharib, Samir (1998). One Hundred Years of Fine Arts in Egypt. Cairo: Prism Publications.

Videkanic, Bojana (2020). Nonaligned Modernism: Socialist Postcolonial Aesthetics in Yugoslavia, 1945-1985. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Winegar, Jessica (2006). Creative Reckoning: The Politics of Art and Culture in Contemporary Egypt. Stanford: University of Stanford Press.

Zuhur, Sherifa (2001). Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Dance, Music, and the Visual Arts of the Middle East. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Biography

Karim Zidan is an investigative journalist, creative writer, and freelance translator with bylines at The Guardian, Foreign Policy, VOX Media, Open Democracy, among others. He is also Menhat Helmy’s grandson and the manager of her artistic estate.

How to cite this testimonial: Karim Zidan, "Engraved on the Heart: Remembering Menhat Helmy, Egypt’s forgotten pioneer", Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA Region, 8 March 2020, https://manazir.art/blog/engraved-heart-remembering-menhat-helmy-egypts-forgotten-pioneer-menhat-helmy-zidan