Review – Natasha Gasparian, Commitment in the Artistic Practice of Aref El-Rayess: The Changing of Horses

Charlotte Bank, University of Kassel

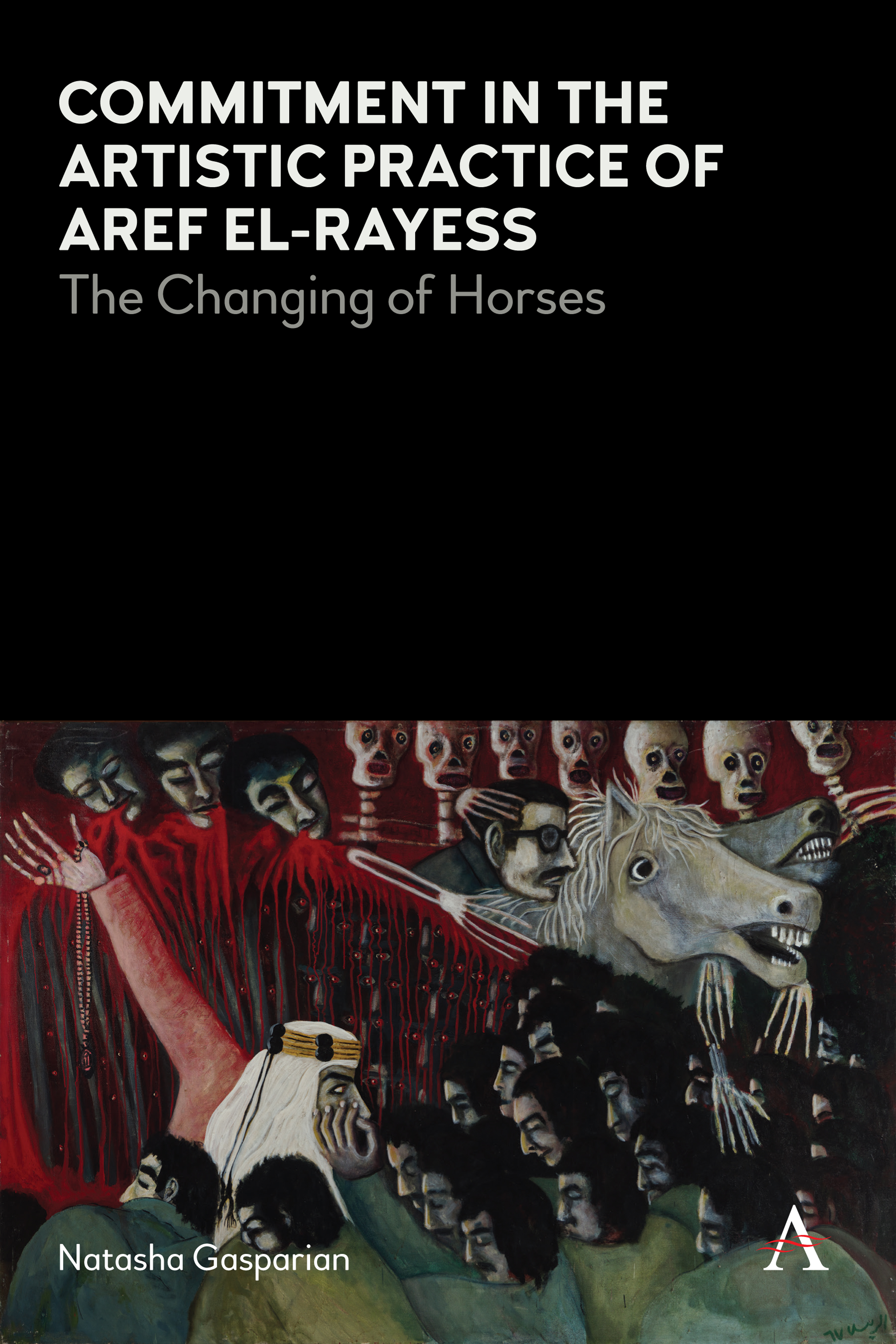

Natasha Gasparian’s Commitment in the Artistic Practice of Aref El-Rayess: The Changing of Horses (Anthem Press, 2020) is the first volume in a planned series published by AMCA (Association for Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World, Iran and Turkey) in collaboration with Anthem Press, New York. In it, the author discusses the history of the Lebanese artist Aref El-Rayess’ painting The 5th of June / The Changing of Horses, which was exhibited together with twelve other paintings in the artist’s solo show Dimaʾ wa Hurriyya (Blood and Freedom) in 1968. The painting was produced under the impression of the Arab defeat in the war of June 1967 (or Six-Day War) and, as Gasparian points out, it is the work with which the artist “publicly declared his artistic and political commitments” (2). As pointed out by Gasparian, the work appears like a realist history painting at first sight, but also has strong allegorical and idealist connotations. For the artist, it represented the “memory of the defeat” (12), but Gasparian also convincingly places the work in the geo-political context of its production. The book examines the work of El-Rayess (1928-2005) together with the exhibitions in which it was shown and the artist’s writings as an example of his committed artistic practice. At a time, where new conflicts in Lebanon are in focus, together with artists’ responses to the upheaval, the book offers a glimpse into the country’s recent socio-cultural and socio-political history and how artists of previous generations engaged with and commented on the local and regional conflicts and wars.

The main part of the book is divided into three chapters, entitled: “The Exhibition”, “The Artist” and “The Reception”. The first chapter discusses the context of the exhibition “Blood and Freedom”, which took place at Salle de L’Orient in Beirut in April 1968. While The 5th of June / The Changing of Horses was the central piece of the show, other works paid homage to such diverse figures as Che Guevara, Martin Luther King, Charles de Gaulle, Palestinian fida’iyin or represented scenes of struggle in Lebanon, Palestine and Vietnam. The location of the exhibition space in central Beirut guaranteed a diverse audience, and due to its political content, the show was said to have been the exhibition with the highest number of visitors till that date. It went on to be exhibited at other venues in Lebanon, where the artist made a point of giving tours of the exhibition and offering ample information material as a way to engage his audiences. Against this background, Natasha Gasparian traces the events that led to the formation of El-Rayess’ politically committed stance. Shocked by the war, he had wanted to engage himself in the struggle, if possible as a soldier, but was refused due to his lack of military training. He was told, though, that he could best serve the cause through his work as an artist.

The second chapter, entitled “The Artist” offers an examination of El-Rayess’ understanding of artistic commitment, as expressed in a number of statements written in what Gasparian calls a “romantic, anti-capitalist” mood (17). It begins with an elaboration of the intellectual debates around the concept of “commitment” that took place in the Arab world since the 1940s, which were stimulated, amongst other texts, by Jean-Paul Sartre’s writing on engagement (translated into Arabic as iltizam in 1947 by the Egyptian literary critic Taha Husayn). The concept became hugely influential in the Arab world in the following decades and the Beirut-based literary journal al-Adab was particularly significant for promoting the notion of commitment in literature.

The debates around the notion of “commitment” and its implications in the Arab world are important to understand the intellectual and artistic climate within which Aref El-Rayess was working. And it is the particular situation in Lebanon that is of special interest here, as this country is rarely considered in studies of artistic commitment in the Arab world. However, when reading the very elaborate discussion of the debates on commitment in intellectual and literary circles of the Arab world as reconstructed by Gasparian one might wonder if this part of the book could have been cut short and the interested reader instead referred to further literature by scholars such as Ibrahim M. Abu Rabiʿ, Yoav Di-Capua and Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab, whom the author cites in her study, in order to place more focus on the Lebanese context. But Gasparian also offers some new reflections on this crucial period. While most scholars tend to regard the war of June 1967 as a radical rupture leading to new forms of political and social projects, Gasparian diverts from this view. Instead, she treats the event as “the result of an intensification of already-existing, though repressed, social and economic contradictions in Lebanon (the high point of which was the outbreak of the Civil War in 1975) and in the region within a singular, asynchronous capitalist modernity” (20), something that strikes me as a thought-provoking and very interesting argument in this particular Lebanese context.

The chapter goes on to elaborate how El-Rayess’ position on the artist’s role was formed in this intellectual climate and how his revolutionary ideals resonated with the position of the journal al-Adab. Its co-editor, Suhayl Idriss, published an editorial entitled “al-Adib fi al-Maʿraka!” (The Writer in Battle) after the defeat of 1967, signalling a turn towards a more radicalized, revolutionary stance on the social commitment of artists, writers and intellectuals. Aref El-Rayess followed this conviction and expressed his views, according to which the role of the committed artist and intellectual was to challenge the existing social order and to represent “the will of the people”, in his own writing and public appearances. It was also reflected in his participation in numerous exhibitions, events and initiatives that expressed support for anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and anti-Zionist positions. Aref El-Rayess saw himself as a revolutionary figure and also represented himself as such in The Changing of Horses as a man on a horse, a “new horse” as he stressed in his commentary to the painting (22, 33), leading the way into the future. He was also active on a regional basis and was a founding member of the General Union of Arab Artists, while also nurturing relations to committed artists throughout the Arab world.

On a more personal level, El-Rayess placed high value on his own notion of authenticity as an artist, seeking to live according to his beliefs and values. One consequence of this was the decision not to show his committed works in private galleries, a choice that was surely not easy for an artist who sought to derive at least a part of his income from the sales of his art works. For Aref El-Rayess, the “authentic artist” was “a fida’i in his everyday life” (28), one who dares to produce a radical art aimed at awakening the “drugged, defeated, and duped out of their torpor” (29). Not favouring particular formal qualities and stressing content over form, El-Rayess called for artists to fight depictions of the world that were untruthful and to make social realities visible. Gasparian refers to this stance as “painterly humanism” and points to similar attitudes among El-Rayess’ Syrian contemporaries Nazir Nabaa, Elias Zayat, Naim Ismail and Fateh al-Mouddares (30).

The third chapter of the book centres on the reception of the painting with a focus on Aref El-Rayess’ own efforts to bring the work closer to the wider audiences as it was presented in a series of exhibitions, held at different locations in Lebanon. Aref El-Rayess usually referred to The Changing of Horses as The 5th of June, a title that would have made the commemorative aspect and political implications of the painting clear to the viewers. He also gave frequent tours of the exhibitions where the work was shown and provided ample textual material, in which he explained the content of the work. These efforts can all be seen in the light of El-Rayess’ adherence to a Sartrean understanding of commitment. But rather than accept the explications of the artwork provided by El-Rayess, Gasparian goes on to point to certain tensions inherent in the painting and its relation to the social reality it was produced in. She discusses the different groups of people represented in the painting and stresses their relation to the material reality in the Arab world, thus identifying the intellectual, the people, fighters and soldiers as well as the Saudi king Faisal bin Abdulaziz al-Saud. While the historical references would have been recognized by the audiences, El-Rayess had provided an allegorical reading of the painting and this was followed by most critics, even though other paintings in the exhibitions seem to have garnered more interest. When commenting on The Changing of Horses, visitors and critics evoked feelings of discomfort and dread. Faced with the nightmarish visions of the piece and assigned it a resemblance with works by Hieronymus Bosch and Francisco Goya. In short, the painting was seen as a representation of hell rather than a comment on current reality. Outlining the debates around the exhibition, Gasparian points to the problematic on viewing a painting like The Changing of Horses outside of ideology. For visitors and critics, it seems, the painting served either as a model of mature artistic commitment or proof of the failure of the concept, depending on their own ideological stance. At the same time, the painting remained enigmatic for most viewers, located somewhere between realism and allegory.

Aref El-Rayess seems to have become somewhat disillusioned by art’s capacities to actually change social issues later on in his career, although he did not leave his committed attitude entirely behind, either. In her conclusion, Natasha Gasparian discusses different aspects of the artist’s later practice, presenting the reader with a well-rounded picture of an artist of renown, who deserves to be wider known to audiences outside Lebanon.

Gasparian’s Commitment in the Artistic Practice of Aref El-Rayess: The Changing of Horses provides valuable context of the production and significance of one of Aref El-Rayess’ central paintings and the exhibitions in which it was shown. Alongside images of the artist’s works, the book offers documentary images of posters and exhibition views, as well as photos of the artist’s other activities, such as visits to training camps of the fida’iyin. Together, all this gives the readers important contextual information. It is rare to find such rich material surrounding one artistic event in one place and, as every person working in the context of the history of modern art in non-Western locations will appreciate, locating and accessing relevant material is not always an easy task. This makes the reader look forward to the upcoming books in the series and hope that more scholars will examine other significant art works and exhibitions in an equally close way. The discussion of the role of commitment in art and literature in Lebanon with examples of different critics’ texts is also a valuable contribution to scholarship on modern and contemporary art of the Arab world, as commitment is rarely discussed in the context of modern art in Lebanon.

However, faced with the rigorous research that clearly has gone into writing this book, one might wonder why some minor, but easily avoidable, puzzling points have not been corrected in the editing process. There is occasionally some inconsistency in the writing of names, which will not pose a problem for readers who are familiar with Arabic, but might be confusing to non-Arabic speakers (e.g. at times the street where one gallery was located is written Shāriʿ Trablus, at other times Shāriʿ Trablos). In the interest of furthering the study of global, non-Western modernity across linguistic barriers, it is in our interest as scholars to pay attention to such details. Likewise, Gasparian has chosen to use the term “the masses” very frequently, possibly as a wish to follow Aref Al-Rayess’ and his contemporaries’ designation of society’s unprivileged and marginalized groups of people. However, the frequency with which this happens appears somewhat anachronistic, and the use of the term throughout the book leaves the reader with a wish to know more about this choice, if it was deliberately made.

Certain points of the analytic reading of Aref El-Rayess’ painting could also have merited further discussion. In particular, the affiliation between El-Rayess’ work and the Mexican socialist realist painter David Alfaro Siqueiros (13-14), with whom Gasparian sees a shared a concern for “the masses” would have been interesting to pursue more deeply and clarify whether this is a general observation about the painter’s practice or whether the author is referring to one particular painting of the Mexican artist. The Mexican muralists are often mentioned by Arab artists and art historians as important influences for committed art, a point which is also interesting in the context of south-south leftist solidarity. Including this aspect in Gasparian’s discussion of Aref El-Rayess’ connection to the Mexican artists would have added an important dimension to the artist and his work. This minor criticism notwithstanding, the book remains a compelling and enjoyable reading and offers an example of how art historical research can lead us to understand not only the aesthetic aspects of art, but also the intellectual and political climate of a period and its cultural production.

Biography

Charlotte Bank is an art historian and independent curator. She holds a PhD in Arabic culture from the University of Geneva and has held academic positions and fellowships at the Universities of Bamberg and Geneva, the Orient Institute Beirut and the International Scholarship Program at the Museum of Islamic Art Berlin / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Her monograph, titled The Contemporary Art Scene in Syria: Social Critique and an Artistic Movement was published in 2020 at Routledge. Since August 2021 she is postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Art and Society at the University of Kassel.

As a curator specialized in the modern and contemporary art of the Middle East, she has worked with numerous institutions in Europe and the Middle East and in 2012 established the artistic project space Art-Lab Berlin.

How to cite this review: Charlotte Bank, "Review – Natasha Gasparian: Commitment in the Artistic Practice of Aref El-Rayess: The Changing of Horses", Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA Region, 1 September 2021, https://manazir.art/blog/natasha-gasparian-commitment-artistic-practice-aref-el-rayess-changing-horses-bank