AWRAQ 19th issue: an initiative for the study of Arab modern and contemporary art in Spain

Review of Awraq 19th issue, “Los tiempos del arte árabe moderno y contemporáneo” [The Times of Modern and Contemporary Arab Art].

María Gómez López, Universidad Complutense de Madrid

That modern and contemporary art from the Arab world has seen a growing international interest in the last decades comes as no surprise when reviewing the number of exhibitions, publications, seminars and congresses devoted to it. The increasing presence of artworks in different parts of the globe produced by artists from, based in or somehow related to the so-called Arab world has accordingly encouraged a proliferating academic activity. This activity aims at critically navigating a production often thought of as coming out of nowhere. In other words, specialized studies are progressively delineating a necessary genealogy of a bustling contemporary creation with clear roots in movements, proposals and cultural scenes from previous decades.

The massive presence of art from the region has not escaped Spanish institutions such as MACBA – Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, IVAM – Institut Valencià d'Art Modern in Valencia, CAAC – Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Seville or MNCARS – Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. However, this lively activity in museums, galleries or art centers hardly finds any echoes in the academic field, where modern and contemporary courses in art history programs do not examine the context of the Arab world and rarely overcome the 15th century when studying Islamic art. Moreover, programs with a focus on the MENA region relegate artistic production to a second place, where it operates as a medium to understand varied sociopolitical issues. This vacuum is being addressed by varied individuals, institutions and initiatives that claim for the importance of in-depth studies in modern and contemporary art from the Arab world, not exclusively for its possible role as a tool to examine political, religious or economic matters, but especially for their radical aesthetic and discursive contributions to global art history. AWRAQ’s 19th publication definitely belongs to these initiatives.

AWRAQ was founded in 1978 as part of the Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura, the Spanish-Arab Cultural Institute. In 2012, Casa Árabe would take over the journal, turning AWRAQ into an organ of dissemination of its main activities and missions. With its headquarters in Córdoba and Madrid, Casa Árabe is a strategic center for the relationship of Spain and the Arab countries. As specified on its website, it operates as an active platform for Spanish public diplomacy with a multifaceted program articulated around three main axes: Training and Economy, International Relationships and Culture. As part of its cultural program, Casa Árabe organizes a great number of activities that include exhibitions, conferences, seminars, podcasts, book launches, publications, theater or film series. It thus succeeded in providing various entry points to the Arab world for diverse Spanish, Spanish-speaking, and international audiences.

The need to explicitly tackle and critically engage with the modern and contemporary art histories of the region was the main driving force behind AWRAQ’s only issue exclusively devoted to the last decades’ artistic creation. This long awaited project comes not only to fill the previously mentioned vacuum in Spanish academia, but also to bring a Spanish-speaking audience closer to a number of relevant texts in the field, written by a number of senior and junior, Spanish and international scholars. The variety of voices included in the issue and the importance granted to the dissemination of knowledge in different languages, seems to entail a support for a polyglot and polyphonic art history. For that matter, AWRAQ’s issue seems to come in line with a generalized search for more egalitarian and truly global ways of building the narratives, terminologies and methodologies of art history in times of interconnectedness and critical revision of the discipline. Not surprisingly, this revision takes as a starting point the fact that the existence of a single art history is no longer possible if its multiple overlapping stories are to be at last acknowledged.

The title of the issue, “Los tiempos del arte árabe moderno y contemporáneo” [The Times of Modern and Contemporary Arab art] echoes this plurality in a chronological reference that ramifies the linear and homogenous art historical narrative to embrace particular ones. This reference acquires a notable significance in the context of a region that, despite certain commonalities and affinities between its countries, has seen a wide spectrum of divergent and overlapping contexts at a national, local and even individual level. For this reason Nuria Medina states in her introductory article that “plural becomes essential here because, as it is insistently reminded in this and other texts, it turns out impossible to trace a chronological or causal line identical to all this wide geography”. It is with this plural nature of art history in mind that AWRAQ unfolds a palimpsest of events, periods of time, figures, institutions, movements or artworks that point out to some of the pressing debates, relevant questions and possible answers that researchers in the field are facing.

Pedro Martínez Avial, General Director of Casa Árabe, opens the publication with few words that emphasize the relevance of this issue’s subject and how it complements the institution’s performance and mission. His opening letter is followed by Nuria Medina’s introduction, one of the publication’s coordinators and coordinator of Casa Árabe's cultural program. Under the title “El arte desde otro lado” [The Art from Another Side], she examines the effects of last decades’ international interest in the Arab world with a particular focus in its artistic panorama. Medina points out to the unbalanced knowledge production that has seen limited specialized studies with a clear aesthetic and art historical perspective up until very recently, and the massive academic production in other spheres.

The articles that comprise the issue are informally organized in three main groups. The first four articles by Nada Shabout, Silvia Naef, José Miguel Puerta Vílchez and María Gómez López, are general approaches to key issues in modern and contemporary art histories in the region. The following texts, signed by Tiffany Floyd, Nadia Radwan, Rachida Triki, Moulim El Aroussi, Sam Bardaouil, Anahi Alviso-Marino and Tina Sherwell address specific moments in Iraq, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Lebanon, Yemen and Palestine. Two final articles by Ana Crespo and Fernando Rodríguez Mediano close the issue with a focus on the reception of Arab-Islamic artistic heritage in Spain.

With this structure, the editors provide the unfamiliar reader with an initial series of introductory articles that outline some key concepts, events and challenges that surround and conform the field. These are complemented by the following selection of texts that zoom in to specific contexts to delineate particular histories of art within the region.

A Mosaic of Essays on Modern and Contemporary Arab Art

The issue opens with an article written by Nada Shabout, professor at University of Texas, entitled “Repensando el arte árabe contemporáneo” [Rethinking Contemporary Arab Art]. In this article, the author traces not only a modern genealogy to contemporary art, but also a cartography of some of the spaces in which Arab art is today finding its way to a global art history. Navigating four spaces – namely the international scene, the local one, the space inhabited by a diaspora as an intermediate state between the first two, and finally, the space modelled by the market –, Shabout examines how regional and international events affect and politicize art historical narratives. This enables her to tackle how these events redefine in different ways curatorial and institutional stances that affect in turn how artworks circulate.

Shabout’s article is followed by “Representación del legado y la cultura árabes en el arte moderno (de la década de 1940 a 1991)” [Representation of Arab Heritage and Culture in Modern Art (from the 1940s to 1991)] written by Silvia Naef, professor at the University of Geneva and founding member of Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA region. Naef’s article opens with a brief explanation of the three periods she identifies in the history of modernism in the region: a period of adoption (late 19th century), a period of adaptation (1940s to 1991) and a global period (starting in 1991). In her text, she focuses on the adaptation period, defined by a moment of reflection on national identities ignited by the Arab countries’ independences after the Second World War. During those years, many artists moved away from assimilated foreign modern languages, subjects or techniques to explore various ways of articulating a modern Arab art. For this purpose, they would not only turn towards international formulations of modernity, but most importantly towards the reinvention of local heritage and tradition, which gave way to indigenous responses to global phenomena. Naef illustrates this historiographical analysis with specific examples that bring to the fore the main trends of this adaptation period. The author talked about this in the online presentation of the issue that Casa Árabe held.

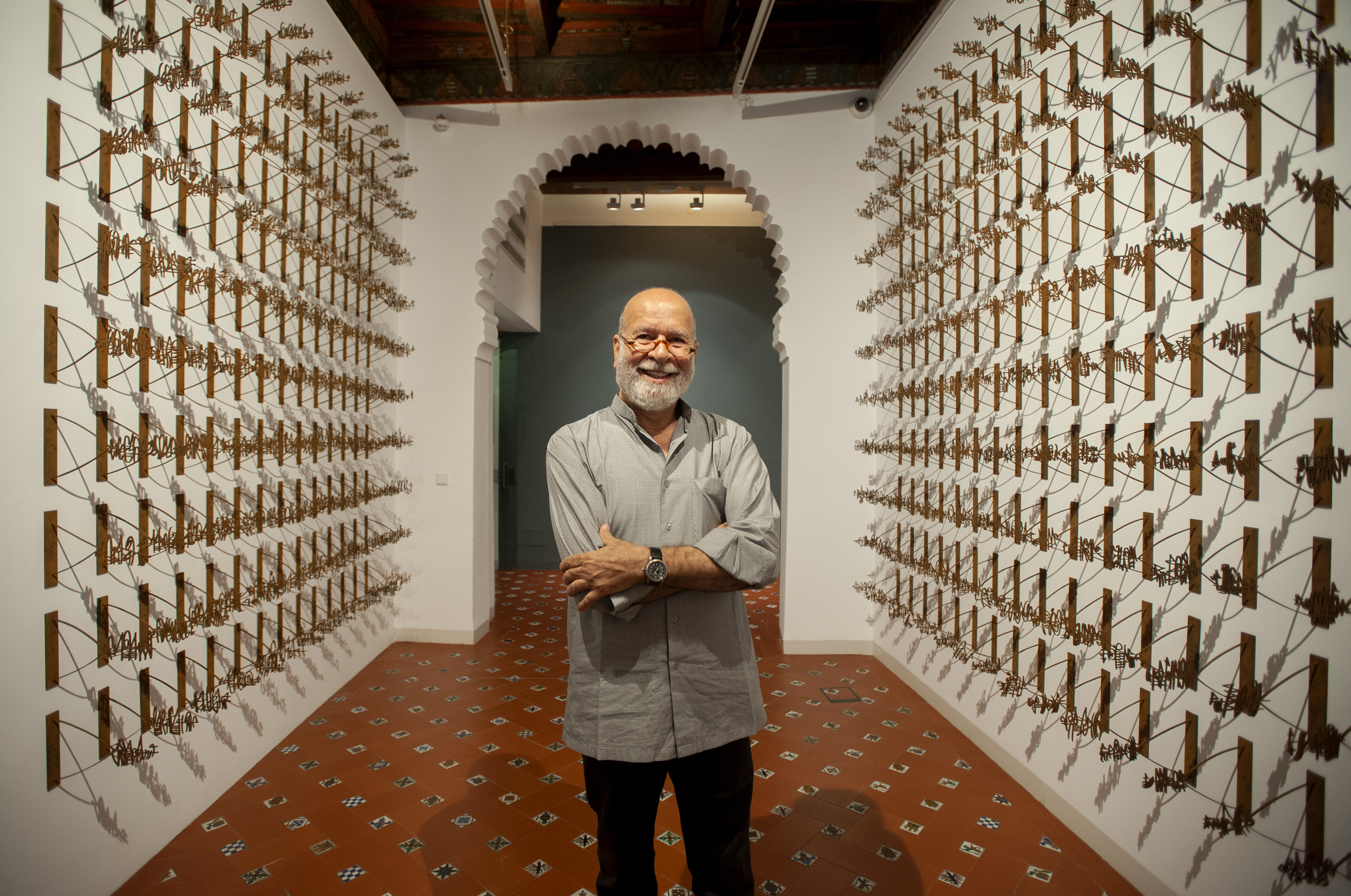

José Miguel Puerta Vílchez, professor at the University of Granada, Spain, traces in “La lengua y el pensamiento árabe clásico en la plástica árabe actual” [Language and Classical Arab Thought in Arab Contemporary Visual Art], the imprint that classical Arab thought and language had in modern artists from the region in a moment when an innovative and committed aesthetic language nurtured from tradition, experimentation and international exchanges, was being articulated. To this purpose, Puerta Vílchez punctuates his text with quotes from philosophical and literary references that, put in dialogue with manifestos and other modern art writings, evidence the artists’ interactions with diverse historical traditions. All these reflections are grounded in the following analysis of some works by Iraqi artist Madiha Omar and Palestinian writer, critic, art historian and artist Kamal Boullata, both of whom turned towards the Arabic letter as part of what in the previous article Silvia Naef stated was the first and only pan-Arab modern trend, hurufiyya.

The fourth article of the issue is written by myself, María Gómez López, a PhD candidate at Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Under the title “Arte y cartografía: narrar el mundo desde los lugares del arte” [Art and Cartography: Narrating the World from the Places of Art] I examine how the reinvention of cartography, broadly understood, in contemporary artistic projects from the region may operate as a response to both canonical ways of telling and defining the territory, and to how we define ourselves in relation to the places we traverse and inhabit. The aim of the article is to track possible plastic responses to a long theoretical debate that questions the currency and logic of an ‘Arab art’ or an art ‘from the Arab world’ today. Considering the presence of similar reflections produced in other parts of the world, I ponder how these artworks, stemming from personal spatial experience and imaginaries, may articulate prospective alternative geographies, art worlds and territorial bonds and representations that challenge and complement more conventional ones.

With her article “El arte modern iraquí y el modernismo global” [Modern Iraqi Art and Global Modernism], PhD candidate at Columbia University Tiffany Floyd reflects on the recent turn to a ‘global modernism’, a proposal that aims at widening modern art narratives by reconsidering the diversity of international artistic trends and exchanges. Under this prism, the author unfolds the advantages of three possible entry points to modern artistic panorama in Iraq in relation to an international context: first, the artists’ formative trips abroad and their return to the country to undertake a teaching and professional activity; second, the analysis of contact zones such as Lisbon, notably with the Calouste Gulbekian Foundation and Baghdad; finally, she examines the transnational relationships stemming from the historical convergence of oil and artistic sectors in 20th century Iraq. Floyd concludes her article by pointing out to other possible approaches to modernism in Iraq and some questions the use of a global modernism framework might pose.

Nadia Radwan, professor at Bern University and co-founder of Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA region, navigates the Egyptian artistic panorama in the first decades of the 20thcentury in her article “Modernismo egipcio y el Cairo como plataforma cultural” [Egyptian Modernism and Cairo as Cultural Platform]. Radwan briefly outlines the colonial impact in the country’s cultural and educational infrastructure and the operations behind a transnational construction of modernism with roots in local heritage. Radwan then focuses in the pioneers’ generation, also known as al-ruwwad, who were trained in local and European institutions and consolidated a transcultural exchange that marked the political movement known as nahda or cultural awakening. This generation would lead the way to what would come in the 1930s and 1940s and their legacy, as Radwan writes by the end of her article, is still alive today in different Egyptian museums and collections, awaiting further research and acknowledgement.

Following the early years of modernism in Tunisia, philosopher, curator and professor at Tunis University Rachida Triki explores the evolution of the artistic panorama in the country from the late 19th century until well into the 20th century in her text “Los comienzos del arte modern en Túnez” [The Beginnings of Modern Art in Tunisia]. From the introduction of easel painting to the founding of the Salon Tunisien or the appearance of the first educative institutions, she follows the proposals of artists like Yahia Turki, Ammar Farhat, Aly Ben Salem or Hatem El Mekki. All moved away from imported academic painting to return to local traditions, daily life, familiar rituals, popular imagery and distinctive techniques and materials to give rise to a homegrown and heterogeneous modern aesthetic response.

Moulim El Aroussi, philosopher, writer and curator collaborating with different universities, brings the reader to Moroccan artistic panorama with his text “Las artes visuales modernas y contemporáneas en Marruecos” [Modern and Contemporary Visual Arts in Morocco]. In this essay, he sharply outlines the intricate relationship of tradition, craftsmanship and art through a modern movement permanently linking the three. He briefly examines the role of French and Spanish colonialism in Moroccan cultural life and the consequent return to local heritage during the second half of the 20th century, with the articulation of a modern artistic language in consonance with indigenous historical background. In a closing paragraph, El Aroussi throws light on the Moroccan artistic scene from the 1990s on, mentioning some of the changes that have consolidated a cultural and educative fabric that has in turn diversified and facilitated artistic production and circulation within and beyond the country.

In “El transmodernismo en una época de excesos: el ejemplo de Beirut” [Transmodernisn in an Era of Excess: the Case of Beirut] curator and co-founder of Art Reoriented Sam Bardaouil looks into the burgeoning art scene in the Lebanese capital between the 1950s and the beginning of the Civil War in 1975. Throughout his text, Bardaouil argues for a transmodern approach that, as he asserts, might enable to transcend postcolonial and orientalist studies to articulate a really transversal understanding of modernism in Lebanon, and more broadly the region, by fully acknowledging its heterogeneity. Bardaouil writes a brief introduction on the arts in the city during the first half of the 20th century to later plunge into the second half to gather many of the local and foreign institutions, people, publications, galleries, museums or educative centers that in those years articulated their particular response to the global phenomenon of modernism. By the end of the article, the author reflects on the definition, intention and possible outcomes of transmodernism as a paradigm that overcomes center-periphery dichotomy and other preconceived frameworks assimilated to the study of modernism.

Moving to Yemen with an article entitled “Haciendo historias visibles: instituciones e historias del arte en Yemen” [Making Histories Visible: Institutions and Art Histories in Yemen], researcher at Labex Futurs Urbains Anahi Alviso-Marino examines the evolution of art spaces and artistic panorama in Yemen from the 1960s until present days. Alviso-Marino takes as a starting point Murad Subay’s street art project, a proposal that turned the city walls into platforms of encounter, exchange and political debate. Alviso-Marino later undertakes an in-depth analysis of state-run and independent art centers and institutions that, closely interwoven with everyday life, have defined the Yemeni cultural scene in the last decade.

The last article with a country focus is signed by Tina Sherwell, assistant professor at Birzeit University, and is entitled “Arte palestino: resistencia y geopolítica” [Palestinian Art: Resistance and Geopolitics]. In her text, Sherwell tackles the challenges Palestinian artists face not only since the foundation of Israel, but also with the internationalization of their creation. After offering a possible definition of Palestinian art, the author unravels the controversies behind a truly global art history, one that now turns, not without polemic, to the until-recently considered peripheral areas. Sherwell examines how Palestinian artists negotiate their place in the overlapping art worlds in which their pieces circulate, sometimes fulfilling, some others overcoming or even turning against certain expectations.

Two closing articles focus on the reception of Arab-Islamic heritage in Spain. Artist and holder of a Ph.D. in Fine Arts, Ana Crespo signs “‘Capaz de acoger todas las formas mi corazón se ha tornado’. Reflejos del sufismo en el arte contemporáneo en España” [‘Capable of Accomodating Every Form my Heart has Become’. Reflections of Sufism in Contemporary Art in Spain]. Her text is a journey through certain key aspects of Sufism and their crystallization in the work of a group of contemporary Spanish artists that include Clara Carvajal, Manuel Aguiar, Isabel Muñoz or Hashim Cabrera. The analysis is articulated around Jayal. La imaginación creadora. El sufismo como fuente de inspiración [Khayal. Creative imagination. Sufism as inspiration source], an exhibition curated by Pablo Benito and coordinated by Nuria Medina in 2016 at Casa Árabe Madrid on this very same topic. The final text is an intervention by Fernando Rodríguez Mediano, research scientist at CSIC (Spanish National Resarch Council), in the round-table “La aportación de la civilización arabo-islámica a Europa ayer y hoy” [The contribution of the Arab-Islamic civilization to Europe yesterday and today] within the seminar Europa mestiza y plural celebrated in 2019 at Casa Árabe Madrid. In the brief comment, Rodríguez Mediano reflects on the connections between the Islamic world and Europe and shares the need of considering both entities an essential part of the other, especially in light of their converging histories.

This AWRAQ issue can be conceived of as a relevant first step towards the development of a scarcely explored field in Spain until now, operating as a possible tool to go beyond the temporal, geographical and conceptual boundaries of academia in order to embrace some spheres that have for long been obliterated. With its first section devoted to key moments, concepts and historical itineraries followed by specific case studies by country, the issue facilitates the reading to an audience that is not familiar with these topics. Nevertheless, the articles also provide knowledgeable readers with a rich collection of essential texts that bring to the fore, in one volume, relevant aspects of the recent research in the field of art history in the region. The pooling of articles by both recognized and emerging scholars that move within and beyond the academic milieu enables to measure the pulse of what is being done today in different parts of the world in relation to Arab art histories.

However, and precisely for the art historical focus of the issue, the reader might miss more images that accompany the texts, not only for mere visual pleasure, but especially to better follow and grasp what the articles explain. One can imagine this absence responds to the difficulties posed by rights management and reproduction permissions, but the publication would have been greatly enriched with them. Together with this scarce imagery, there are also other absences, including many authors that could have taken as well part in the issue, a specialized bibliographical compilation or case studies focused on places like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Syria, Libya or Jordan, with artistic panoramas that well deserve targeted researches.

Nevertheless, an exhaustive review of art historical studies with a focus on modern and contemporary Arab world was not at all the purpose of the issue, which rather operates as a window to what is being done in the field or, as stated in the introduction, as a mosaic. As such, many tiles are still to be gathered and searched for by the reader himself. Let us hope that this window-mosaic is not only a first step for upcoming projects in Spanish-speaking communities, but also the reflection of a growing field that is finding varied spaces of encounter – here in the form of a publication – from where to weave an expanding network of art histories.

Biography

María Gómez López is a PhD candidate in History of Art at Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she holds a FPU-MECD Predoctoral Fellowship. In her dissertation she explores a global convergence of art and cartography in the last decades, with a focus in the crystallization of this phenomenon in contemporary creation from the Arab world. She examines how these proposals, articulated from personal experience, might challenge and complement more conventional means of spatial representation. María did her MA at SOAS University of London and has undertaken research stays at Center for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies (CAMES) – American University in Beirut and the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. The results of her work have been shared in different publications and events.

How to cite this review: María Gómez López, "AWRAQ 19th issue: an initiative for the study of Arab modern and contemporary art in Spain", Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA Region, published online 15 March 2021, https://manazir.art/blog/awraq-19-gomez.