Nostalgia and Belonging in Art and Architecture

from the MENA Region

Essay Collection

Research project conceptualized and edited

by Laura Hindelang and Nadia Radwan

This collection brings together twelve short essays investigating how nostalgia and belonging come into play in the study of modern and contemporary art and architecture from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Each essay focuses on one selected object—a work of art or architecture—and reflects on its relation to the overall theme.

The essays in this publication result from the research seminar “Nostalgia and Belonging: Art and Architecture in the Middle East and North Africa, 19th–21st Century”, which we taught together at the Institute of Art History at the University of Bern in spring 2021. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all classes were held via Zoom. Merging our respective fields of research and interests in visual arts, architecture, and heritage, we designed the seminar in a transdisciplinary perspective to investigate the current buzz words “nostalgia” and “belonging”, which have increasingly informed the discourse on cultural production in the countries of the MENA region without being comprehensively situated and examined. Our goal was to close this gap by bringing the study of modern and contemporary art and architecture of the MENA region into a fruitful and open dialogue with the conceptualization of nostalgia and belonging in academic writing. This endeavor was informed by recent reflections on global art histories and the decentering of the discipline (for example Keshmirshekan 2011; DaCosta Kaufmann et al. 2016;), which has raised questions about the ways in which the canons, theories, and methods of traditional western art history can be expanded or even reconsidered to adequately incorporate cultural productions from the MENA region.

Essays

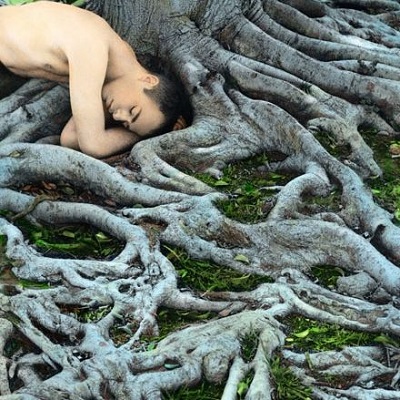

Nostalgia (from the Greek nostos, return, and algos, longing) was first coined by the physician Johannes Hofer to describe the extreme homesickness felt by Swiss mercenaries in the late seventeenth century. It has since been theorized as a dialectic relationship between past and future across various disciplines in the social sciences and humanities (Davis 1979; Boym 2001). From the mid-2000s onwards, the meaning of nostalgia has been debated in the fields of modern and contemporary art and architecture (Foster 2004; Huyssen 2006; Bishop 2013). This development is linked to the fact that a growing number of artists and architects have introduced practices for revisiting, archiving, unearthing, reimagining, and deconstructing both past and present in order to create decolonial, vernacular, and transnational approaches of cultures, knowledge production, and politics.

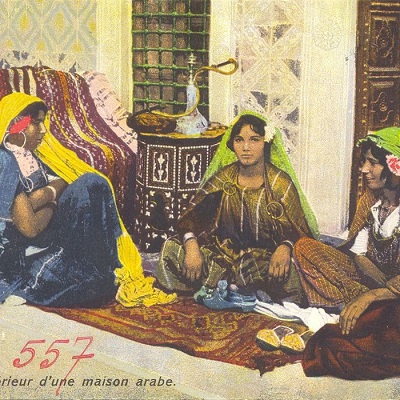

Overall, Svetlana Boym’s The Future of Nostalgia has emerged as a key text on the topic, especially for the field of art and architectural history, as she also discusses practices such as heritage making, collecting, archiving, and exhibiting. In her book, Boym defines nostalgia as “a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed” and “a sentiment of loss and displacement”, but also as “a romance with one’s own fantasy” (Boym XIII). Boym’s definition of nostalgia opens up multiple perspectives on a complex phenomenon and seems to resonate in both the real and imagined geography of the MENA region, which has been romanticized from the nineteenth century onwards. Furthermore, Boym situates nostalgia as an individual or collective reaction towards the unsettling experience of modernity. While in Hofer’s days nostalgia was considered to be a “treatable sickness”, Boym argues that by the twentieth century it had become an “incurable disease”, because “nostalgia, like progress, is dependent on the modern conception of unrepeatable and irreversible time” (7, 13). The MENA region as a space that is crucial for the constitution of European (art) histories has generated multiple stories of modernism and its contestations. The “nostalgic turn” has also opened up fruitful ways to examine modernisms, as underlined by Claire Bishop’s insightful question: “How did we get so nostalgic for Modernism?” (2013). Curious to investigate the deeper meaning of this “turn”, we have taken debates surrounding the terms nostalgia and belonging as an incentive to reflect on their relationship with (post)colonialism, orientalism, and nation-building. From this perspective, it became clear to us that nostalgia and belonging cannot be understood as being fixed in the past, but rather that they are processes that fluctuate and change across real and imagined localities and temporalities. This aspect has also been emphasized by Nira Yuval-Davies, who in her work on the politics of belonging argues that “even in its most stable ‘primordial’ forms, however, belonging is always a dynamic process, not a reified fixity, which is only a naturalized construction of a particular hegemonic form of power relations.” (Yuval-Davies 199).

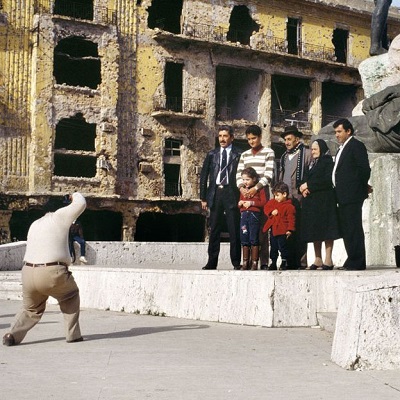

Throughout the semester, the sessions brought forward an impressive diversity of genres and objects of investigation (paintings, installations, photography, architectural drawings, monuments, social housing projects), practices (art-making, drawing, building, curating, archiving), and geographies (Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates). Each of the case studies we discussed shed light on a new aspect of nostalgia and belonging, expanding the reflection to such topics as melancholia and sadness, commemoration and memory, migration and exile, trauma and loss, nation-building and identity, fragmentation and restoration, and mimicry and authenticity. The resulting collection of essays is proof that nostalgia and belonging are fruitful concepts for the study of art and architecture from the MENA region, particularly because they are complex and multirelational.

Among the many relevant questions that emerged from the discussions and brainstorming sessions on objects of art and architecture with our students were the following: Is nostalgia dependent on space and/or time? Who seeks to induce nostalgia, and with which intentions? Is nostalgia something that emanates from the artist’s/architect’s intention or biography, or is it instead expressed by the theme, form, and atmosphere of the artwork? To what extent is nostalgia triggered by questions of subjectivity and positionality? Which audiences does nostalgia concern? Does the place of exhibition or the lived experiences of the viewers matter? Is nostalgia invoked as part of the afterlife (German: Eigenleben) of the art/architecture object or as part of the reception through audiences, collectors, critics, and scholars?

Discussions around nostalgia frequently test the timelines and chronologies that we as art and architectural historians apply, forcing us on the one hand to be very precise and very context-specific with labels such as vernacular, ancient, traditional, futuristic, modern, and contemporary, and on the other to draw (often incommensurable) connections between past, present, and future. For example, one question raised in the seminar was whether nostalgia means having a faith in the past or future that needs to be constructed, maintained, and archived. Moreover, our discussions tested and affirmed the notions of nostalgia and belonging as both concept and sentiment, oscillating between the scientific method and the emotion linked to lived experience. In the geographic context of the MENA region, these notions resonate in both the collective/individual memory of the colonial past and in collective/individual trajectories in the postcolonial present.

The study of modern and contemporary art and architecture in the MENA region cannot avoid examining the complicated relationships with colonial experiences and heritage or questions of center and periphery. Consequently, nostalgia relates to the challenge of the binary discourse typical of orientalism as critiqued by Edward Said. The intractable meandering between local and universal and between east and west is part of the production of the “orient” as a concept rather than as geography. Given that being an artist/architect from the MENA region has become a valuable but also very much contested and often very emotional marker, nostalgia may open the path to new ways of considering the product of transcultural encounters. In this respect, nostalgia and belonging are not only relevant themes but, more importantly, are also useful conceptual tools for analyzing the construction of narratives, emotion, and meaning in art, architecture, and cultural heritage.

References

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. Basic Books, 2001.

Bishop, Claire. “How did we get so nostalgic for modernism?” fotomuseum winthertur blog, 14 Oct. 2013, https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/2013/09/14/how-did-we-get-so-nostalgic-for-modernism/. Accessed 1 July 2020.

DaCosta Kaufmann, Thomas, et al., editors. Circulations in the Global History of Art. Routledge, 2016.

Davis, Fred. “Nostalgia, Identity and the Current Nostalgia Wave.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 11, no. 2, 1977, pp. 414–24.

Foster, Hal. “An Archival Impulse.” October, no. 110, Autumn 2004.

Huyssen, Andreas. “Nostalgia for Ruins.” Grey Room, no. 23, 2006, pp. 6–21.

Keshmirshekan, Hamid, editor. Contemporary Art from the Middle East: Regional Interactions with Global Art Discourses. I. B. Tauris, 2011.

Yuval-Davis, Nira. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice, vol. 40, no. 3, 2006, pp. 197–214.

Cover: Céline Burnand, Retour à Helwan – La Maison des vivants, 2021 © Céline Burnand.

Copy editing: Markus Fiebig.

Published with the support of the “Inspirierte Lehre” (Inspired Teaching) grant of the University of Bern.

Biographies

How to cite this research project: Laura Hindelang & Nadia Radwan (eds.), "Nostalgia and Belonging in Art and Architecture from the MENA Region. A Collection of Essay", Manazir: Swiss Platform for the Study of Visual Arts, Architecture and Heritage in the MENA Region, 18 October 2021, https://www.manazir.art/blog/nostalgia-and-belonging-art-and-architecture-mena-region