Blog

Manazir's academic blog was curated by the editorial team of Manazir Journal from 2019 to 2024, and was conceived as a space of exchange and expression.

We invited submissions of exhibition, book and conference reviews and particularly encouraged reviews that focused on events or publications produced in the MENA region itself. Moreover, in connection to Manazir's endeavor to shed light on art histories in the MENA region, we welcomed submissions of "testimonials" from family members and friends of artists, architects, archaeologists, collectors and curators who have played an important role in their field.

As part of her exhibition at the WS Art Gallery in Porrentruy (Switzerland), Elham Etemadi, an Iranian painter based in France, answered some questions regarding the creation of her paintings. These are often large and vibrantly coloured canvases, creating a fantastic universe featuring big rides, broken-down cubes forming labyrinths, and men and women with faces of dogs and rabbits. Beyond inviting contemplation, her artworks have the power to inspire and leave a lasting impression on the viewer.

Based on a historical and poetic reading of the tumultuous early period of Arab-Islamic civilization, this exhibition is an artistic exploration that questions the images, forms and socio-political issues that characterize it, while placing them in the perspective of their resonance with today’s context. The curator Nadine Atallah adopted the Arabic notion of fitna relating to the ideas of disorder, discord and sedition. With its strong political and religious connotations this notion acts as a common thread enabling her to weave the formal and conceptual links that structure this large-scale exhibition.

The exhibition The Walls of Burhan Doğançay is organised by the MAH in collaboration with the Kunst Museum Winterthur. It is made possible by the generosity of Angela Doğançay, the artist’s widow, who, in 2018, made a significant gift of fifty-nine works of the artist to the MAH. The exhibition focuses on the series Walls of Israel which dates back to 1975 and the artist’s first trip to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Barely two years had passed since the Yom Kippour War (October 6–24, 1973) and the work reveals both the political context and the dominant mindset in the country at the time. This trip was the starting point of Doğançay’s major artistic, photographic, and archival endeavour, Walls of the World, which was his focus until the end of his life. This unique archive, consisting of over forty-thousand photographs from 114 countries, is presently housed at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis. Based on this material and sketches, Doğançay built an oeuvre of works on paper and paintings that represent, reframe, rework, and reinterpret walls from the four corners of the world, all while revealing shared aspirations and a universal language.

“Michael Rakowitz, Réapparitions” is the first solo show in France dedicated to the Chicago-based Iraki-American artist. Michael Rakowitz’ artworks are politically, and socially engaged and embedded in geopolitical issues. This exhibition, which takes place at the 49 Nord 6 Est – FRAC Lorraine, is dedicated to his series The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (2007-ongoing). The artworks relate to archeological heritage from Iraq which has been looted, destroyed, or illicitly trafficked since 2003. The artist tries to recreate the lost objects, thanks to several sources of documentation. His creations are thought to be “ghosts” of the originals. He also addresses the experience of exile and of belonging to the diaspora in relation to objects and people. The program scheduled by the FRAC Lorraine during the exhibition extended Michael Rakowitz’ perspectives with other points of view, both personal and academic.

This testimonial examines the pioneering Lebanese sculptor Youssef Hoyek, whose work remains largely understudied.

His artworks and archives are currently scattered and neglected. There are no official archives or museums that collect his work. This has been possibly affected by the political instability that Lebanon has been undergoing since the death of Hoyek more than sixty years ago.

This testimonial aims to highlight Youssef Hoyek’s work and is based on the research I undertook in Lebanon and abroad for my doctoral thesis. Its aim is to contribute to the writing of the history of modern art in Lebanon and the region, through a rapid overview of unpublished and largely unknown material.

Review of the exhibition “Mirrored Reflections: A Study of Transformations in Iranian Contemporary Art (1974-1984)”, curated by the independent researcher Kianoosh Motaghedi at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in January 2022. The exhibition is a selection of works from the revolutionary and war period by Iranian artists from different groups, shown furthermore through a larger movement that is protest art, started before the advent of the revolution.

Estelle Sohier reviews Charles Genequand’s book, which examines the biography of Max van Berchem (1863-1921). Just 100 years ago, Max van Berchem (1863-1921) died of illness and exhaustion, days before his 58th birthday. This man known by only few in Geneva today, is the founding scholar of Arabic epigraphy, in other words the study of inscriptions in Arabic. This text reviews the life of a man who described himself as an orientalist, showing his attachment to a field of study that no longer exists as such today.

Charlotte Bank reviews Natasha Gasparian’s book, which examines the work of El-Rayess (1928-2005) together with the exhibitions in which it was shown and the artist’s writings as an example of his committed artistic practice. At a time, where new conflicts in Lebanon are in focus, together with artists’ responses to the upheaval, the book offers a glimpse into the country’s recent socio-cultural and socio-political history and how artists of previous generations engaged with and commented on the local and regional conflicts and wars.

This collection brings together twelve short essays investigating how nostalgia and belonging come into play in the study of modern and contemporary art and architecture from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Each essay focuses on one selected object—a work of art or architecture—and reflects on its relation to the overall theme, showing that nostalgia and belonging are not only relevant themes but, more importantly, are also useful conceptual tools for analyzing the construction of narratives, emotion, and meaning in art, architecture, and cultural heritage of the MENA region.

Inheriting an artist's collection and archive is an extraordinary adventure, which reshapes one's own history. But how should one manage, (re-)organize and archive works and documents, when one is neither an art historian nor an archivist?" It is in these words that Christine Abboud, daughter of the painter Shafic Abboud (1926-2004), describes the challenges of archival work and the desire not to betray the work and life of her father.

The exhibition "En attendant Omar Gatlato: Regard sur l'art en Algérie et dans sa diaspora" (Waiting for Omar Gatlato: Focus on art in Algeria and its diaspora) celebrates twenty-nine Algerian artists spanning sixty years of art. Curated by Natasha Marie Llorens it takes place at the Triangle France – Astérides center of contemporary art in Marseilles. The artworks show another way of looking at the individual and collective histories a multicultural and complex Algeria.

Display cases with books and documents, photo collages on the walls, a model skyscraper made of rusty file boxes stacked on top of each other. The installation "Indépendence Tchao" by the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia at the Kunsthaus Zürich builds a complex web of relationships that examines the causes and origins of modern architecture in a extra-European context, not least to ask whether and to what extent the dream of the future ought to be assigned to the past. A review.

AWRAQ: Revista de análisis y pensamiento sobre el mundo árabe e islámico contemporáneo is a journal that focuses on different aspects of the Arab world edited by Casa Árabe, a strategic center for the relationship of Spain and the Arab countries with headquarters in Córdoba and Madrid. Under the title “Los tiempos del arte árabe moderno y contemporáneo”, its 19th issue gathers for the first time a collection of relevant texts on modern and contemporary art history from the Arab world in Spanish. Some of these texts have been previously published and were translated and others were commissioned and published for the first time. These essays offer a broad overview of a field that is yet underdeveloped in Spanish academia.

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, many cultural institutions, such as galleries and museums, had to cancel and/or postpone their activities. Therefore, the artists and the institutions are disconnected from their audience. To keep in touch with his fellow Iraqi artists, the London-based Iraqi artist Dia Azzawi founded the online magazine Makou (There isn’t) in May 2020. By providing a platform specialized in contemporary Iraqi art, Makou describes itself as a “free zone of creativity”. The first issue of the magazine focuses on the pandemic and its consequences on art production.

What is an “Islamic” thing? In Waren Welt Islam (Commodity World Islam) Alina Kokoschka examines the life world of “Islamic” things, consumer culture, and the aesthetics of commodities in the context of Syria, Lebanon and Turkey. Laura Hindelang talks with Alina Kokoschka about the book, brands and brand fakes, and open science.

Read the report of the symposium “Images absentes, images détruites: une approche comparatiste?” to discover, through an original journey among different cultures and epochs, the rather transnational and trans historical character of iconoclasm and aniconism, as well as the most common reasons underlying them.

Firouzeh Saghafi conducted an interview with the director of Datsan’s Basement, Hormoz Hematian, to get his view on the art situation in Iran in times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To celebrate the centenary of the Bauhaus, the Zentrum Paul Klee presented the show "bauhaus imaginista" which addresses the cosmopolitan history of a modernity resulting from cultural exchanges and transfers. This review focuses on the Maghreb section of the exhibition "Decolonize Culture: Casablanca Fine Arts 1962-1970".

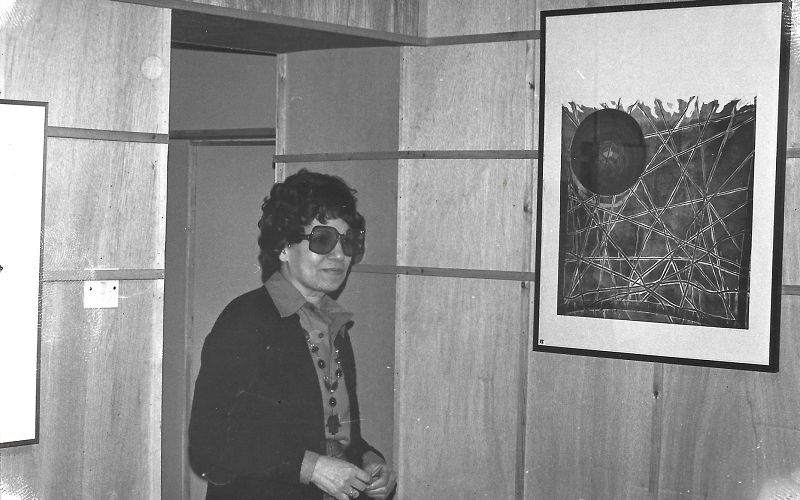

Menhat Helmy (1925–2004) was a pioneering figure in the world of Egyptian graphics and printmaking. Her work, which ranged from oil on canvas to colourful abstract etchings and woodcuts, made her a key figure in her field and led to a long list of awards and international achievements. Following her retirement and eventual death in 2004, Helmy joined the ranks of countless female artists lost to history – a forgotten gem in a landscape dominated by male artists.

Review of the exhibition "Serpent Dream" by French artist Tarek Lakhrissi which took place at Zabriskie Point, a Geneva art centre in the public space. "Serpent Dream" is the second solo exhibition of Lakhrissi who decided to focus on interaction with the public through a multimedia installation.